home | toki pona taso | essays | stories | weasel | resources | stuff I like | about | linjamanka | give | linguistics | tok pisin

essays home | dictionary | direction | what is pona | what is toki pona | semantic spaces | lupa rambles | lanpan and nimisin | toki pona cookbook manifesto | FAQ | teaching tips

(By A♭)

teaching tip number one: avoid using “is”

because toki pona’s words are so vague, this is especially important. learners will be grasping for single words or phrases to represent english concepts, and saying that a word is or means something rather than a word can be or can mean something helps cement that lexicalization. use your best judgement.

Why: There are multiple ways to say everything in toki pona. Saying “is” instead of “can be” makes it seem like there’s only one and stifles creativity. Instead of engaging the part of the brain that uses context to disambiguate, it engages the part of the brain that remembers words and meanings, which isn’t bad per say but isn’t effective teaching for toki pona.

AVOID

learner: “what’s the word for door?”

teacher: “lupa.”

REASONABLE

learner: “what’s the word for door?”

teacher: “I usually use lupa.”

BETTER

learner: “what’s the word for door?”

teacher: “lupa is a good option because it can easily be interpreted as a doorway, but if you’re talking about the flat part of the door itself and not the concept of a doorway, kiwen, supa, or sinpin might be good words to use.”

if you’re pressed on time though, a simple “lupa can work” might suffice here, or “i recommend lupa,” or “i see lupa a lot.” Just avoid saying “lupa” on its own or giving a direct translation without including the word “can” in there. Additionally, saying “pu lists ‘door’ under ‘lupa’” could work here very well.

tip number two: don’t give it away! let them say it.

Often beginners will ask for a translation of a phrase. Simply giving them a translation might not always help them learn. Instead, give some ideas of words you might use in a construction, ask pointed questions, and evaluate how much help with grammar they might need.

Why: This engages mechanisms in the brain that learn more effectively. If you want to learn more, see tip number ten.

DON’T

learner: “how might I say I dropped an egg on the ground and it broke in toki pona?”

teacher: "You could say a sike waso mi li kama anpa li pakala."

DO

learner: “how might I say I dropped an egg on the ground and it broke in toki pona?”

teacher: “well, there’s no word for drop in toki pona. How might you rephrase this sentence without having to talk about the act of dropping? Maybe describe it from the perspective of the egg?”

the teacher goes on to engage learner in a dialogue and leads them to create the sentence themselves

tip number three: stick to the head

If a learner asks a question about a phrase with multiple modifiers, answer their question first by talking about if the concept fits into the semantic space of the head without its modifiers. then, tackle the modifiers one by one and explain how they might further specify.

Why: This kind of teaching can go a long way to discourage lexicalization.

FINE

learner: “does tomo tawa mean car?”

teacher: “yes! tomo tawa can mean car”

BETTER

learner: “does tomo tawa mean car?”

teacher: “yes! a tomo can be a car, and specifying that it’s moving is a great way to make that clear if it wasn’t already clear from context.”

tip number four: use simple words!

Surprisingly, toki ponists often use jargon words in english while teaching. of course use your best judgement and adapt to your learner, but avoiding jargon is a good way to make sure your teachings are accessible to any learner to talk to.

Why: Many learners don’t know any of the jargon you might use!

DON’T

learner: “how do i use wile?”

teacher: “well you see, wile is a preverb, so it goes before the predicate, similar to auxiliary verbs. wile specifically specifies verbal modality to a degree, showing that instead of preforming the predicate (wether that be derived through toki pona’s derivational patterns or a base meaning) you desire to do the predicate. do you have any questions?”

DO

learner: “how do i use wile?”

teacher: “wile is a preverb. it goes before the verb. so if you put it before the verb in any sentence, it changes the meaning from do the thing to want to do the thing. do you have any other questions about preverbs or does that make sense?”

tip number five: give examples

Contrast two statements and design them such that the beginner can play around with replacing words. you don’t have to do this every time but it’s ridiculously helpful. you don’t need to give examples if they already understand the base concept, so make sure to ask if you aren’t sure. NOTE: you do not need to always do this. It can be somewhat labor intensive.

Why: Examples are among the most helpful things for learners.

FINE

learner: “how does tawa work?”

teacher: “tawa shows the direction the action is towards. it’s a preposition.”

BETTER

learner: “how does tawa work?”

teacher: “first, do you know how prepositions work in toki pona?”

learner: “no.”

teacher: “so prepositions give extra information about the sentence. they mark the words after them as having specific relation to the sentence. tawa shows direction, what something is for, etc. so for example mi pana e sike could be i throw the ball, but if we want to specify in what direction, we could say mi pana e sike TAWA SINA, which could be i throw the ball TO YOU. when tawa is the verb, it serves as both a verb and a preposition. mi tawa sina could be i go to you, because tawa means “go” as a verb. something like mi tawa tawa sina is redundant and i hardly see it used.”

tip number six: try to be patient, or take a break.

if you ever find yourself frustrated at a learner for not understanding a concept, there’s no shame in taking a step back and just not teaching. we all get irritable and impatient every now and then, and there’s nothing wrong with that, as long as we don’t make it a learner’s problem. now if a beginner is frustrating you for some other reason, by all means use best judgement and call them out on it, like if they’re being bigoted, or if they bring up primitivism, or if they argue back. but if you don’t think you’ll be able to teach with kindness, don’t teach at all. call for other teachers to teach if there’s nobody else around.

now, if you ARE ABLE to notice your own irritability in these situations and correct for them, do that instead! Take some breaths, observe what’s going on, and come at teaching from a new angle. Look at some inspirational quotes online about patience until you’re sick of them.

Why: Feeling frustrated can discourage a beginner from continuing learning toki pona, and sometimes it really is just the teacher’s fault. Don’t be That Guy™️.

DON’T

learner: “I still don’t get it. how does la work?”

teacher: “what’s not clicking? i explained it to you like three times already.”

DO

learner: “i still don’t get it. how does la work?”

teacher: “hey, can any other teachers try to explain? i need to take a break.”

DO

learner: “i still don’t get it. how does la work?”

teacher: takes a deep breath, collects thoughts, reëvaluates their teaching methods. “can you be a bit more specific? what exactly isn’t clicking? i want to help you understand.”

tip number seven: make connections.

One of the most helpful things in learning is making connections. If you’re teaching about one concept, relate it to a different one. The more connections made, the better the concepts are remembered by the learner.

Why: Learning is, in many ways, your brain making connections between things. If you make some connections for people, that can help them learn better.

OKAY

learner: “I thought luka just meant hand, but I saw someone use it as a verb. What does that mean?”

teacher: “oh luka can mean touch.”

BETTER

learner: “I thought luka just meant hand, but I saw someone use it as a verb. What does that mean?”

teacher: “any word that means a noun can be used as a verb. Its meaning is apply [noun] to the thing. So for example, with luka it could be touch, punch, pet, slap, etc. For noka, it could be stepping on something or kicking.”

Tip number eight: facilitate learning instead of controlling it.

Let the learner guide you. Answer their questions. Provoke their mind and help them learn, but don’t control what they’re learning. They came to you with a question, and as a teacher you’re there to answer it and help them learn. The main goal of teaching is to do this.

Tip number nine: avoid talking about “correct” usage

Avoid saying that certain usages are standard or correct. If a usage is incorrect enough for you to say so, surely there’s a reason, be that a simple “nobody uses it like this” or a “this is discouraged.” Reasons why something isn’t or is “correct” are often simple enough that you can just teach those instead. In a pinch, there’s not much harm it can do, but what you consider “standard” might be a bit arbitrary for a living language, and as a teacher you should be evaluating what you mean when you say the words you say. Be descriptive.

Why: Evaluating some usage as correct and other usage as incorrect is somewhat prescriptive, i.e. you are prescribing language. A simple change in word choice can fix this.

DON’T

learner: "when a sentence starts with mi or sina, I know that you don’t use a li for the first verb, but would you use li for a second one? Such as mi moku li olin e sina.

teacher: “No, that usage is incorrect.” OR “Yes, that usage is correct.”

AVOID

learner: "when a sentence starts with mi or sina, I know that you don’t use a li for the first verb, but would you use li for a second one? Such as mi moku li olin e sina.

teacher: “Sure, but it’s not the standard way to do it.”

BETTER

learner: "when a sentence starts with mi or sina, I know that you don’t use a li for the first verb, but would you use li for a second one? Such as mi moku li olin e sina.

teacher: “Yeah, that usage is common! Some people don’t like it as much because it’s just as easy to say mi moku. mi olin e sina. But nonetheless it’s still done a lot and you’ll be understood.”

Tip number ten: tell a story

There are studies that show that knowledge is retained better when there is some emotion or story tied to it. If possible, tell a story. Some ideas:

- Tell a story about a relevant misconception you had about toki pona, and what clicked to make you understand the concept better. For example, I often tell people how I thought toki pona was really easy when I started out, and about a year in I realized that my self-assessment of my fluency had been inaccurate for most of it.

- Tell a story that gives an example of why a misconception is incorrect. For example, I often bring up how I learned what a derivative was in toki pona when people claim you can’t talk about math in it.

- Teach things in a creative way! The more interesting an example you have, the more interested someone will be in what you have to say, and the more likely they’ll remember it. Be a novel experience.

- Go off topic! “But then I’m not teaching anymore!” Okay! Cool! You’re helping learners feel comfortable in toki pona spaces and it will make them feel more comfortable asking questions in the future. Ultimately, getting distracted doesn’t hurt learning.

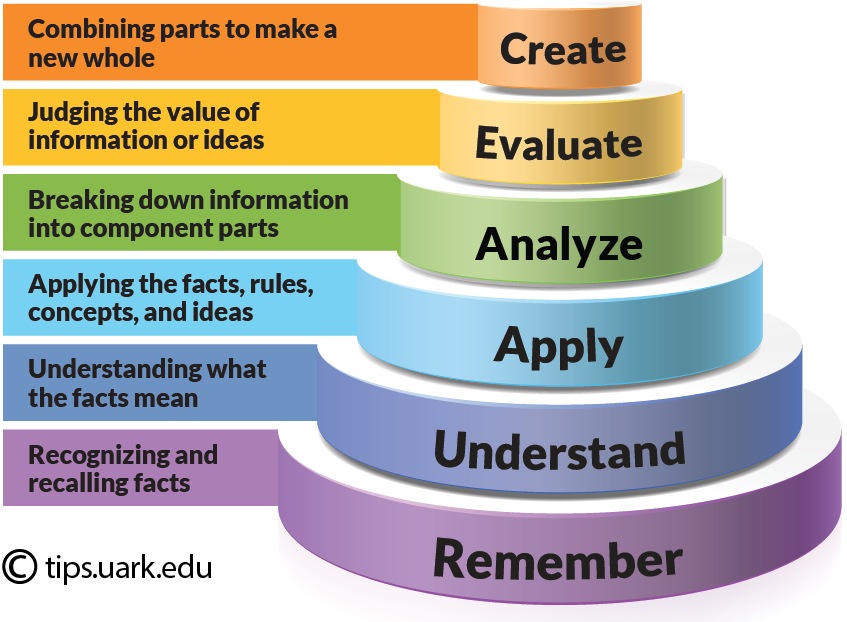

Tip number eleven: use bloom’s taxonomy

This one is kind of advanced lol. There’s a lot of good info in here but it might be a headache so I put it last, feel free to skim or not read at all.

Why: This is evidence based educational psychology. It works!

In educational psychology, there’s a tool called “Bloom’s Taxonomy” which I’ll try to summarize here. It separates learning into six categories, shown below. The ones closer to the bottom are easier to do for a learner, but aren’t as effective. The ones at the top take more effort, but more effective. All of these have their place in teaching toki pona.

I’ll give examples of how each of these might be used in toki pona learning settings, and what you can do to facilitate those activities.

CREATE: A learner tries to write a journal entry in toki pona. (A teacher might point out spots that didn’t make sense and offer ways to rephrase it or concepts to play around with)

EVALUATE: A learner and a teacher discuss why toki pona doesn’t have its own word for “think,” and discuss possible alternatives. (A teacher might ask questions and lead the learner to a realization about toki pona)

ANALYZE: A learner tries to decipher a sentence in toki pona and translate it back into English. (A teacher may offer feedback, correct the learner, etc.)

APPLY: A learner goes walking outside and points to objects around them, thinking of what toki pona words they’d use to describe those things. (If this is offline, doing this with a learner could be remarkably helpful)

UNDERSTAND: A learner attempts to teach other learners (which should be encouraged, by teachers! Teachers might facilitate this by finding parts of a learner’s statement to agree with, point them out, and then add more nuance as needed. The shit sandwich is a good tool here too - sandwich negative criticism between two pieces of positive criticism.)

REMEMBER: A learner uses flash cards to memorize the vocabulary. (Simply suggesting a high quality anki deck might be good for this one, but if it’s a friend sometimes I sit down with them and tell them fun things I like about each word one by one.)

If something seems like it’s too easy for a learner, try to suggest something higher up in the pyramid. If something is too daunting, try to move something down a bit. For all of these, your role as a teacher is to facilitate an activity done by the learner, as I’ve shown above in parenthesis. These strategies are broadly applicable to other activities in the same category.

tip number twelve: don’t follow my tips to a T

These aren’t rules, they’re tips. if you feel that your teaching style doesn’t mesh well with these tools, then do not use them! You’re a teacher, which means you know what you’re doing. Or maybe you’re not a teacher and you don’t know what you’re doing. either way, only use the tips if they feel right. try them out.

Why: I am not omniscient.