Part one, the Qwamaq language, can be found here.

Part two, Journey to Rising City, can be found here.

Join the Qwamaqqar discord server!

Read the Qwammaq grammar!

Take a look at the Qwamaq lexicon!

Expand/Collapse All

Recap (Jan 6th 2025 1:00 AM)

I found a book while looking through my grandfather's things that gave instructions to open a gateway to another world.

Through the gateway, I met Zhoniker and his family, members of the Qwamaq ethnic group and speakers of the Qwamaq language.

Zhoniker and I went to a large city called Konoprar and moved in with Zhoniker's bio father.

A wisdom holder of the city showed me a document about my great great aunt Dora Lipman, who went missing in 1953. The document mentioned that she may move to a different city called Ullipar.

It's been a busy couple of months! Finals caught up to me. I think I did well enough. In any case, I should give a brief update on what's been going on with Zhoniker and Qwamaqqar.

Zhoniker has been teaching me a very small amount of Olsem. My Olsem is still pretty bad, but at this point it's safe to say that Olsem and Qwamaq are related. They both have trigger systems, and the classifiers in Olsem very closely remember the nominalizers in Qwamaq.

The most apt example of this I can think of right now is fek, which is a classifier for tools. In Qwamaq, /-faq/ is an instrumental nominalizer suffix. There are some ones that may be related but seem more opaque.

Olsem also has a noun class system. I still can't figure out if it has any basis or is completely arbitrary, but apparently I am in class A, along with every other person i've met except for some Olsem who are in class B. Though people in class B are sometimes in class A. That is the only reasonable pattern I've been able to find, all other objects seem to be arbitrary.

So why am I learning Olsem? Pretty simple! Actually no it's very complicated. So let me run over what happened. Zhoniker and I went back to Porer after I finished translating the document about Dora, and I asked her where further information would be. She took me down a different path in the catacombs, but in the room she took me to, the tablet she was looking for had gone missing. After looking around for it in the room, she noticed a coin on the floor.

Apparently, these coins belong to Olsem families. They mint these coins and carry them in pouches. They're not really used for trade, but the more you have from your own family, the more status you have within that family. Olsem families are apparently pretty large. If you kill someone from a different family, you must carry all of their coins with your own. Killing other Olsem (and killing in general) is taboo. Manslaughter is considered different, I think? I may elaborate if and when I meet an Olsem person who can explain it to me.

But what's relevant here is that whoever took this second document likely dropped this coin. some Olsem have been known to steal from the catacombs and sell documents to other Olsem to put in their "mountain home," which is a place in the mountains where the Olsem return to for the … winter solstice? There are two solstices of course but I'm not sure which one just happened a couple of months ago. They keep family belongings that they can't bring with them in special sacred hiding spots, basically. They are normally nomadic and move every four days, but they stay in their mountain home for a whole month. They decorate their camps with all sorts of treasures. Qwamaq tablets are prized decorations.

So essentially, I will need to journey to the mountains with Zhoniker. We will have to bring the door with us so I can easily return home, which sounds really inconvenient, and we'll need to get there before the next solstice (the mountain one). But most Olsem are apparently really strong. Must be carrying all those things around with them all the time. So Zhoniker is looking around town for an Olsem guide. We will leave within four days.

Before I leave though, I have been wanting to meet with the fortune teller. I have seen magic working in real time here, and if there's a chance I can learn more about what happened to Dora from this, I should try it out. Potentially, I'd like to visit the house of relics to see if they have anything before I leave Konoprar for the mountains. Zhoniker has confirmed to me that such a fortune teller exists, and that they he can take me to them.

Now I'm thinking: what if I make a much lighter door so Zhoniker and I can carry it around with us? like an inflatable one or something that can unfold or something? That way, we can have access to Matar and Konoprar, as well as wherever Zhoniker is at the time, all through my world. idk how doable that is. Signing off for now.

Jan 7th 2025 12:25 AM: The Fortune Teller

I've been wearing traditional Qwamaq clothing, with a catch: it's customary for foreigners to wear flowers in their hair, as a sort of marker. This seems to be because the Qwamaq shave their heads, but the Olsem all grow it out, and apparently so do other foreigners, but I've yet to see anyone who isn't Qwamaq or Olsem.

The Olsem have been moving through Konoprar on their way to the mountains. They avoid it for the solstice because their religion seems to discourage any worship or celebration not in honor of the chaos god they worship? But that may not be entirely accurate and it may not be quite that strict.

In any case, Zhoniker and I went to the fortune teller. Cataracts studded his eyes like cracks in three-year-old vegan leather. He squinted to see us. He was wearing a pale cream sarong. He greeted us: "tak ono tar Toraper tar Zhoniker Papolarosh Pamatar" (I encounter Toraper and Zhoniker of the shard of Matar). I still can't fathom how he knew our names, but he IS a diviner.

Every single wall had shelves installed all the way up to the ceiling, and each of these shelves was filled with labeled clay and glass jars. The glass ones were filled with liquids, powders, and various other semisolids. There was a block of salt on a lower shelf with a plethora of geodes and crystals. It was very dark inside the room. It kind of reminded me of my own abundance of spice cabinets at home.

"esiˈpakaŋŋa" (sit down), he said, gesturing to two chairs. There was no table, only stools carved of wood. It seemed he neither time, energy, nor desire or motive to sand them or wax them or have someone else do so for him, because were it not for my clothing, I would have gotten many splinters. Zhoniker was silent, so I followed his lead.

After several of the longest sort of seconds, he spoke. "esiˈʒaŋa anʃi ʃuqa fu qaˈmel?" (are you here in the room?)

Zhoniker affirmed with a simple "esiˈʒaŋa ampar" (we are) and I repeated after him.

"tʃiˈkeʃi anʃi fufu fol?" (what do you want to know about?) As he asked, he turned around, squinting at his shelves, feeling his stones, searching.

Zhoniker gestured toward me with what in Anglophone culture could be called a "shoo," but I've come to learn that it means "go ahead" among the Qwamaq. So I spoke. "tʃiˈtumus ono fu toraˌtoraˈper. ʃoˈkuri fufu tʃiˈkeʃi oʃi. esiˈmiʃ oʒa fu fol?" (Dora Lipman is my ancestor. Maybe you know. What happened to her?)

The fortune teller looked towards me, though it was unclear whether or not he could make eye contact with me. "toˈsari oʃi fin tumus fu esalaˈlinʃ papamˈpaka. koroka. tʃiˈkeʃi oʃi fufu toˈkor mekeˈnel maʃa paˈmolli fufu tʃitumus un tar ʃannaˈper paˈmaʃa." (You use the word "tumus" to describe your relationship. That means you must know that because you are spun from her thread, you alone are able to read it.)

Zhoniker spoke. "ʃoˈmaŋi fufu ʃopiˌmekenʃanˈnanʃ fu kanʃ papaˌnolseˈmer paˌmisiˈrer." (But reading threads is a task of the Olsem and their god of chaos).

The fortune teller handed the smooth turquoise stone to Zhoniker. "miˈqami fu Zhoniker Papolarosh Pamatar. ʃoˈponki fufu ʃoˈpuri toraˈper tatar aʃaˈqami fu toraˌtoraˈper. ʃoˈmaŋi fufu tʃiˈpalor qap tar fiɴqipoʃ paˌnataˈler paˈpampaka. toˈporem tatar tʃiˈkeʃi oʃi fufu esiˈʒaŋa tar aɴqwamaˈqer tar anˌolseˈmer fu qaʃufˌsensoˈfaq. ʃaŋka esiˈtumus fu rasimoʃ tar aŋkaˈper fim aˌnolseˈmer fim aɴqwamaˈqer. ʃoˈka fu aŋkaˌpaŋkaˈper. tʃiˌtakaˌpaʃikaˈpanʃ tar misiˈrer papaˌnolseˈmer tar nataler paˈpaɴqwamaˈqer." (Zhoniker of the shard of Matar. If Toraper wants to speak to Toratoraper, the ways of our spirits cannot help. You must understand that we and the Olsem have occupied the same fabric. Once, at a time, a people spun the Olsem and the Qwamaq into threads. A single people did that. Our spirits and their god of chaos are different interpretations of the embroidery of the world.)

Note: the word tʃiˌtakaˌpaʃikaˈpanʃ can be split into the roots taka and paʃika. paʃika just means "different," but taka can mean a bunch of different things and plays into the conceptual metaphor of needles as people and all that. It can mean: (1) to embroider, (2) to move all over the place, and (3) to interpret the natural world, often describing a spiritual system. The whole word is a verb meaning "to be a different act of interpretation of the natural world," but I translated it the way I did so that the deeper metaphor would not be lost through translation.

Zhoniker felt the turquoise stone, smooth and shiny. "aʃaˈqami ono fi twikakaˈpanʃ paˌtakaˈpanʃ" (I have been told of this way of seeing things).

"this way of seeing things" is literally "this embroidering of embroidering" which I think is pretty funny.

The fortune teller turned to me. "koroka tʃiˈkeʃi qap oʃi. ʃoˈpiŋa fufu aʃaˈqami oʃi fufu aʃaˈsel oʃi fu fol" (You do not understand, and that is obvious. But I will tell you where you must go). When older Qwamaq pause to think about phrasing or what to say next, they simply fall silent, and you're supposed to remain quiet and listen, and try not to distract them.

After a longer pause, he continued. "aʃaˈpakil fin ʃannaˈper paˈpiʃ fu ʃannaˈper paˌʃiʃrafaˈfer tar fummolliˈpor. ʃoˈmiŋku fufu eˈsufuŋŋa anʃi fiɱ fuˈlor. aʃaˈqami ono tar nataler fifi esiˈʒaŋa tar ratʃiˌʃiʃraˈper paˌtoraˌtoraˈper fu ipiˈqar paˌporitʃiˈpar. ʃoˈmaŋi fufu tʃiˈkeʃi qap par tar esiˈʒaŋa anʒa fu fol. ratʃiˌʃiʃraˈper paˌtoraˌtoraˈper." (Only a Fulor* can tie your thread to the thread of a dead person. Thus, find a Fulor. The spirits have told me that Dora's bones are buried near Oritʃipar, but exactly where, I do not know.)

*Zhoniker later tried to explain what a Fulor was to me, but he kept saying "akakiper papanolsemer," so maybe they're kind of like the wisdom holders of Konoprar? But beyond that he doesn't seem too sure. All the more reason to find an Olsem guide who can take us to the mountains. I was also supposed to know that bones would allow a Fulor to connect me to Dora so we could speak to each other, which I didn't obviously.

I thanked the fortune teller, and Zhoniker did as well. Apparently, similar to songwalkers, the fortune teller does not get paid for his work. The community takes care of him. It's pretty nice, and not at all what I'd expect from a city of this size.

In other news, Zhoniker tells me he's met an Olsem travelling alone staying in Konoprar on their way to the mountains. He'll introduce me to them tomorrow or something. They just got here yesterday, and they would love to guide us to the part of the mountains when they get going in three days when they leave. He says I'll probably like them, but when I ask him why, he says "because of a far away tree" before smirking. So I guess I'll see.

Finally, Zhoniker says he would like to take me to the house of artifacts before we leave for the mountains. We'll be doing that tomorrow, and the Olsem is coming with us apparently! It'll be fun.

Jan 8 2025 12:00 PM: The House of Artifacts

I had. SO much fun at the house of artifacts. I have a lot to talk about oh my god.

The Olsem person we met is named [dʒaʎtʃau] (which I'll romanize as Dzhagltshau from now on). She speaks Qwamaq very well, and immediately started asking me about which languages I spoke! As soon as I mentioned English, my native language, without missing a beat, she asked me to teach it to her. Then I said "I speak a lot of other languages too," and she said something along the lines of "well, teach me those too!"

So she's into languages. Which is amazing. I'm into languages!! This must be what Zhoniker meant when he said I'd like her.

Dzhagltshau is probably under five feet tall, but she's strong as hell, just as Zhoniker predicted. Quite the shtarker! She had apparently set up camp with a few more Olsem she didn't know very well outside the walls of Konoprar, but she brought her most important belongings with her, and she didn't seem bothered by the weight at all.

She had a very strong and robust voice and lots of energy, way more than any Qwamaq I've seen, who tend to be more reserved with their emotions. In fact, her voice was not only resonant, but it was so deep that it was lower than mine! For context, I'm a pretty high tenor.

I will admit that my spoken Qwamaq is still kind of shaky. I need to think a lot before I say things. But she was not only engaged with every moment of our conversation, but incredibly patient. I think speaking with her for the few hours we spent at the house of artifacts boosted my Qwamaq more than a whole month of talking to Zhoniker. Maybe I'm exaggerating. But for real, the Qwamaq are brief and calm, but the Olsem just go on and on. At least from what I can tell.

The NEXT big thing is that I found… a Torah?? I think??? It's a scroll, it's big, and it has hebrew written on it. We're not allowed to touch it, but I could recognize some words. Including… t'hom. Which is. Interesting. This warrants further research, but I don't really have much time right now. I'm about to go on a quick vacation, meaning that I can't visit Qwamaqqar between the 12th and the 20th. At all.

I took pictures, but with Uqumer's portable doors, I should still be able to return whenever I want to Konoprar without too much trouble. So I'll take a look at it when I can, but my Hebrew sans niqqud is not very good, the writing is very very old and not very legible, and I am busy. So that will come eventually, not soon. Not to mention I can only see the part that the scroll is opened to. The title on the side of the scroll reads "ספר תהום" which means "book of the abyss," which both sounds metal as fuck. But there's nothing called that in the torah or the rest of the tanakh. So this may be an entirely new book?

Zhoniker showed me and Dzhagltshau an orb that apparently belonged to a very famous songwalker centuries ago. According to legend, the famous songwalker sealed spirits inside of it with layers of paint. In between each layer of paint, they would draw countless tiny circles and force spirits to enter them, and then cover them up. Each new layer trapped the layers beneath it, increasing the power of the orb's energy, until the songwalker was able to "flap." Zhoniker used the root /fuli/ which means "flap like a bird," which becomes "puliper" which means "bird" usually. So.. they was able to fly? Not quite sure, Zhoniker doesn't have more specifics.

Apparently, destroying the orb releases all the spirits, who become indebted to the releaser. Zhoniker told me that he only knew this because Akakiper Pamatar told him, and most people don't know. And it's not "ethical" (lit. "in the clean worldview") to keep all the spirits trapped inside the orb. But he can't smash the orb without people getting incredibly angry with him for destroying a priceless artifact.

Those are the only important things we did that I feel like mentioning. I think we're going to get along really well. If you have any questions you would like me to ask Akakiper tomorrow, please contact me as soon as possible to insure that I am able to ask her!

Jan 9 2025 9:38 PM: Quick return to Matar

Today, instead of visiting Konoprar, I went to Matar to ask Uqumer to make me a more portable door. She said that it would be ready in just one day. That's about all I did today. Short update! Akakiper is doing well, so are the children.

jan 10 2025: An Ancient Path

Uqumer finished the portable door! I thanked her and returned to Konoprar, and Dzhagltshau, Zhoniker, and I set out. Uqumer's portable door opens to a bathroom in a local public library. Unfortunately, I have to leave Saint Paul for a week starting in just two days, so I won't be able to visit Qwamaqqar without … taking the door to my room, Scott's front door, or the public library bathroom door with me on a goddamn plane. So tomorrow's update will be the last before a week-long break.

The path from Konoprar to the mountains is not too long, but once you get to the mountains, reaching the summit can take weeks, especially if you're coming from the south. The path we set out on was ancient. Mounds of stones stewed in the sun beside the road wherever it turned, adorned with what I assumed was an archaic version of the Qwamaq script, only made of logograms. Even Zhoniker struggled to figure out what they said most of the time. No wonder they adapted a rebus. But why the hebrew alphabet?

Dzhagltshau seemed to notice the interest I had in them and told me, trying to mix as many new languages as she could into her sentence, that they were Olsem pictograms! Dzhagltshau couldn't read them either, but she told me she was sure the three of us could figure them out together with the help of a Fulor, potentially. She admitted that she led a pretty secular life personally since she was a "molshtshua," which is a lone nomad who only reconvenes with their family during the few weeks the olsem spend in the mountains. Because of this, she's far from an expert on what Fulors actually do.

The road was well traveled, to be sure. Soon enough, and within a few hours of weary walking, we reached the foot of the mountain. Or, perhaps more accurately, the slope of the land got steeper, and the path began to curve to the side until we were walking between land that went up and land that went down (Dzhagltshau said that in Olsem it's called a "bokwar"). It's hard to know where a mountain's foot truly begins, after all, but it was apparent that we were in them. The sun began to set, and Dzhagltshau sat in the path, grabbing some thick flat stones that could fit in her palm. "apiˈkwikaŋa" (do this), she said. "esiˈkaŋa fim opekˈroʃ fu kumˈpam paˌlalaˈper" (make candles before dark).

Dhagltshau explained to us that the Olsem make candles to keep their hands busy when they stop for the night during a journey. Normally they would do this after setting up camp, but when travelling with a Qwamaq songwalker who can draw a circle shelter, there's no need really.

The Olsem always stop travelling as the sun sets. Maybe if we spent more time walking we would get up the mountain faster, but if it means getting to sleep sooner, I'm not complaining. The reasoning is that the Olsem are to observe more mundane and obscured forms of chaos, and they can only do this through routine. It seems like their concept of chaos is much different from mine. I consider myself an agent of chaos, but for me, that means avoiding and disrupting routine.

The Languages of Toraqar

Knowing that Dzhagltshau was interested in languages, I sat by her as Zhoniker went out in search of fallen wood for a fire. "esiˈʒaŋa tar qamiˌʃuʃuɱˈfaq fu toraˈqar" (There are a large quantity of languages where I'm from).

"ʃoˌpiʃuˈler fu fol? qamiˌwaɱˈfaq? qamiˌqafiˈfaq?" (how many? five? eight?).

I'm still not quite sure how to talk about larger numbers more specifically, so I opted for "oˌqamiˌʃuʃuɱˈfaq" (many more languages).

While I thought she'd be excited, I saw her smile fade. "malli. toˈnus tar qamiˌpeɱˈfaq fu fiɴqifoˈloʃ?" (too much. How will I learn them all?). I suppose I hadn't considered that a possibility.

She told me all the languages she speaks, and says that she has learned every language she could get her hands on, finding pride in knowing what she thought was all languages. But now that she knows both that there is a whole other world full of them through my gateways, AND that one can make their own languages whenever they want like toki pona, she felt her sense of self crumbling. Languages were who she was. She was supposed to know ALL of them.

So I told her the truth, which was that I felt the same way. When I was growing up, I thought there were only a few languages, and that learning all of them was manageable. And I had a similar identity crisis around learning the truth. But I found solace in that I can still learn many languages, and have fun with them. Plus, I said to her, why should one be obligated to learn languages from another world they've never been to?

She is still deadset on me teaching her as much toki pona, English, and Portuguese as I can. Maybe some Tok Pisin, but I don't quite trust myself with that one yet. And seeing how the people of Qwamaqqar have already taught me more than enough of their own languages, I thought it was the least I could do, and committed to it.

My plan for tomorrow is to walk with Dzhagltshau in front of Zhoniker as he songwalks, and try to teach her toki pona through immersion. Either that or I'll teach her all three languages at once. It should be fun no matter what.

I taught her how to say "good night" in all the languages I knew (boa noite, buenas noches, sogni d'oro, good night, gut nakht) as well as a brief conversation about how there is no set phrase for good night in toki pona. She asked me what they all meant, but the only interesting one was the Italian, which means "dream of gold." So I had to try to explain what gold is, and she seemed confused and pointed to her abundant jewelry; I shrugged. I cannot identify gold at all.

Jan 11 2025: Qwamaq Refugees

The Refugees

Today while travelling up the mountain, our path crossed with the path of a group of four Qwamaq: two parents and two children. I was confused: what were Qwamaqs doing by themselves in the Olsem mountains? So after we all introduced each other, as is customary among the Qwamaq, I asked. "esiˈʒaŋa anʃi fu sokaŋoʃuˈler papaˌnolseˈmer fimol?" (why are you in the mountains?)

The one who led the group answered me. I could feel the terror massaged into his bones, and yet I could feel the resilience he wore on his shoulders. "toˈlika ampar fu iʃiˈmar. ʃoˈʒir fufu tʃiˈkifaŋ ŋammapa ano tar sokaŋoʃuˈler emeʃa." (we are fleeing Ishimar. The mountains will be kinder to us, godwilling).

We walked together and exchanged stories. I told them about Dora, and they seemed surprised! One of them even said "fukiŋapa ʃoˈfosol akiŋapa oʃi toraˌtoraˈper!" (I would be lying if I said that Dora was one of your ancestors!) But we showed them the door and that it worked, and they grew to believe me. I told them about where I came from, which was hard because a lot of the things I do day to day don't have words in Qwamaq, but I made do.

After a while, we sort of paired off. Dzhagltshau entertained the children, Zhoniker spoke with their leader, and I spoke with other parent. "ʃotor an fu aˌnoritʃiˈper fimol?" (How did the Oriti hurt you?)

"soˈsukwi par palaŋŋapa. esaˌʃannaˌpalaɴˈqar tar iʃiˈmar fu pwaɴˈqar. unˈpalam tar imiˈpaʃ paˈpampaka fu iʃimemˌpaʃikaˈpaʃ paˈqwamaqˈqar. uˈmaʃika tar iʃiˈmoʃ paˌpiʃiˈmar fu iʃiˌmaʃikaˈpoʃ. ʃoˈtʃila epi. tʃiˈʒif epi. tʃiˈpuri epi tar aˌnoritʃiˈper en qiɱfiqar. ʃoˈmiŋku fufu tʃiˈpakrom an anʒa." (Hear me well. Ishimar is a good settlement in the East. Our pottery is better than all other pottery in Qwamaqqar. The clay in Ishimar is different from other clay. It's soft. It is cleaned and made pure. The Horiti want it for luxury, so they are driving us out.)

In Qwamaq culture, it's customary to show respect through silence, and I assumed this case was no different, so we walked in silence for a while. She seemed to appreciate it. After a couple of minutes I asked: "esiˈmiʃ anʃi fu sokaŋopʃuˈler fimol?" (Why have you come to the mountains?)

"ʃoˈtwaq fu fraˈmanʃ papaˌnolseˈmer papaɴˌqwamaqˈqer. ʃoˈmaŋi fufu ʃoˈmiʃ fu aˌnoritʃiˈper. ʃoˈmiŋku fufu ʃoˈpasoke fu fraɱˈfaq paˈpampaka. ipenta esiˈsel iʒaŋel ampar ʃuqa" (The camaraderie of the Olsem and the Qwamaq has lasted centuries, but the Horiti came, and thus our camaraderie has grown. I have it on good authority that we will be welcomed here.)

I nodded and we fell silent again. It wasn't awkward at all; This kind of stuff happens all the time among the Qwamaq. In fact, sometimes it's considered weird to default to smalltalk. The Qwamaq prefer silence.

Singing Along to the Drum

As we continued up the mountain, Zhoniker began to songwalk. The other Qwamaq walking with us joined in and it turned into a call and response sort of thing. Dzhagltshau didn't participate, but she was still smiling, so it seemed like she enjoyed it.

The song was about the mountains. It used the proper name "sokaŋoʃuler papanolsemer," so my assumption is that it's not sung in different environments. The song was actually about the olsem walking up and down the mountains as the years turn, and about flowers springing up beneath their feet. There were even a few Olsem words in the song that I didn't quite recognize.

It kind of reminds me of songs I sang growing up that would have a few lines of gibberish. Though of course, I expect that everyone present except for me had at least basic knowledge of Olsem. After I got a hang of the pattern, I joined in.

As our song reverberated, I started to see from a new perspective. The style of music made me spot circles in the landscape, and though I couldn't see them with my eyes, I could feel within myself that spirits were appearing in the circles and dancing to our music. They felt like small blue snakes made of energy. I could only feel them faintly at first but after the first ten or so minutes of singing, I could almost see them when I closed my eyes.

Eventually the song had run its course and the Qwamaq returned to silence.

Teaching Dzhagltshau

The Qwamaq prefer to walk silently when there's nothing else to talk about, but the Olsem looove to talk, and Dzhagltshau was no different. She seemed set on pestering me to teach her all of the languages I know, but no pestering was needed! I was happy to oblige immediately.

I would love to transcribe the details of teaching her languages from my world, but it would be an unreasonably complex task. Just know that Dzhagltshau has begun to add English, Portuguese, and toki pona words into her sentences. I will be translating accurately to the meaning going forward.

I asked Dzhagltshau, "tʃiˈkat fufu esiˈkaʃi tar ʒoniˈker fu olseɴˈqar?" (Is it okay for Zhoniker to songwalk here on Olsem land?)

"taː tʃiˈfali tar anolseˈmer fufu kwɐ̃du ʃoˈkaʃi fu qwamaˈqer lon ma papaˌnolseˈmer. bʌt, tʃiˈratʃi qap ampar fufu kwika" (Well, the Olsem appreciate it when a Qwamaq songwalks on Olsem land. But we don't expect this.)

She went on to explain that it's not a part of their spirituality, but the Olsem believe it works because there is ample evidence that it does work. It's a "you can see it" kind of thing.

The Olsem take care of their land too, but it looks very different. They see themselves as an aspect of the chaos of the universe, and to venerate the chaos god is to bring power and growth to the land slowly. There's apparently a smallish mountain that the Olsem avoid for spiritual reasons. Dzhagltshau said it's "too smooth" (firimaˈlanʃ) to venerate? Or something? But it's nearly completely barren, much unlike the ones that surround it, which is evidence that the chaos god worship works.

We continued walking until the sun set, and our group set up camp while the Qwamaq family continued on. The three of us chatted for a while and I said my goodbyes and left Qwamaqqar. As soon as I'm done writing this, I will leave for the airport. I will return to Qwamaqqar on 18th of January! See you then.

Jan 18 2025: Fuck Fuck Fuck Fuck

I just got home and I tried the portal that takes me to the door that Zhoniker and Dzhagltshau are taking up through the mountains and the portal doesn't fucking work. Like I put my hand on the doorknob and it turned but I couldn't open the door. I had to deactivate the portal before the door would open again. I'm closed off. I have no idea what to do. Fuck. Fuck. Fuck fuck fuck FUCK fuck. FuCk.

Jan 19 2025: False Alarm, We Good

Okay apparently Dzhagltshau was sitting on the door lmao. She knows not to do that anymore!

Olsem Cartography

A lot has changed since last I was in Qwamaqqar. Apparently, Dzhagltshau had a map this whole time, but didn't use it. The map confused me because it didn't match up with my understanding of the region.

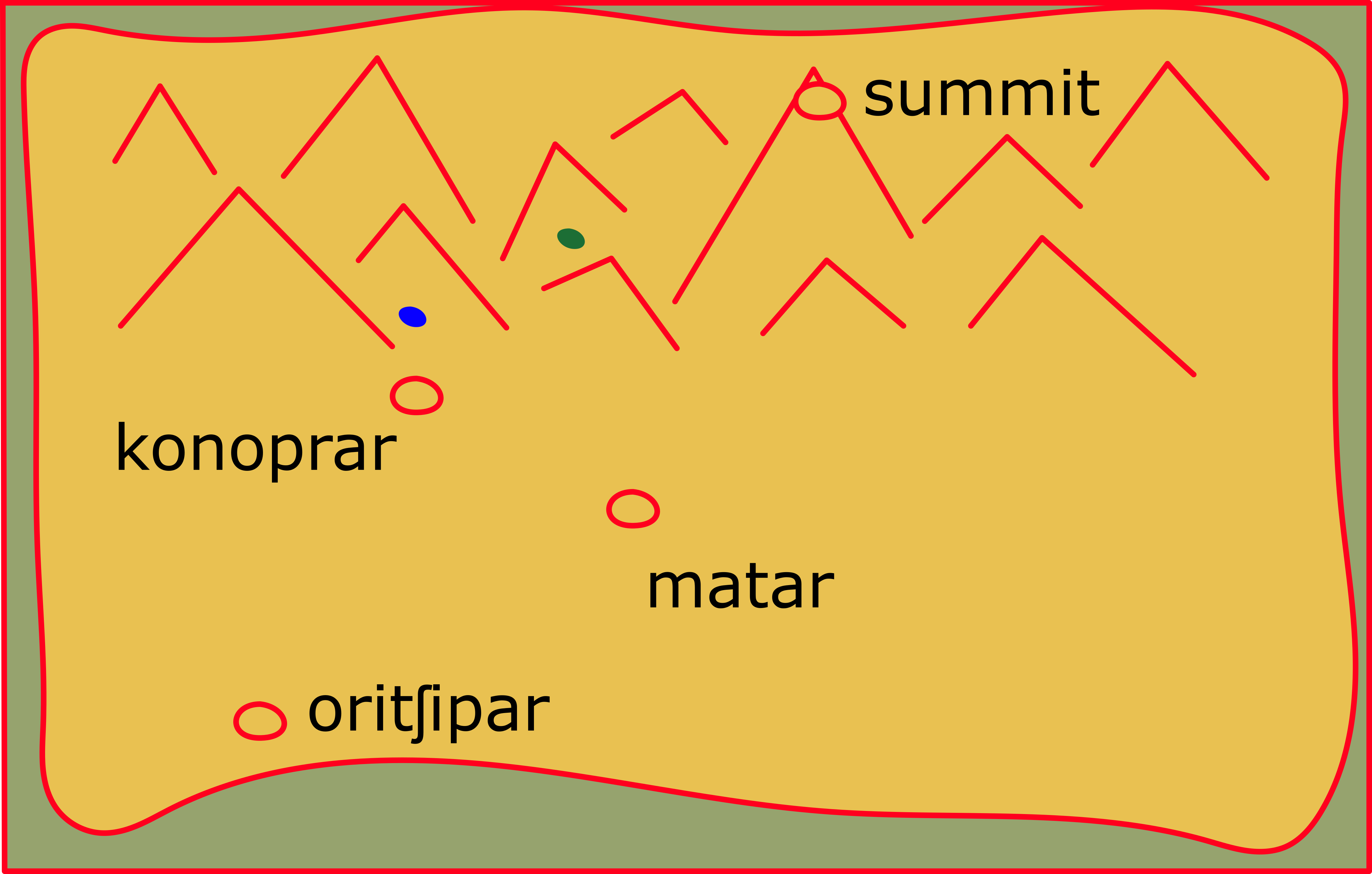

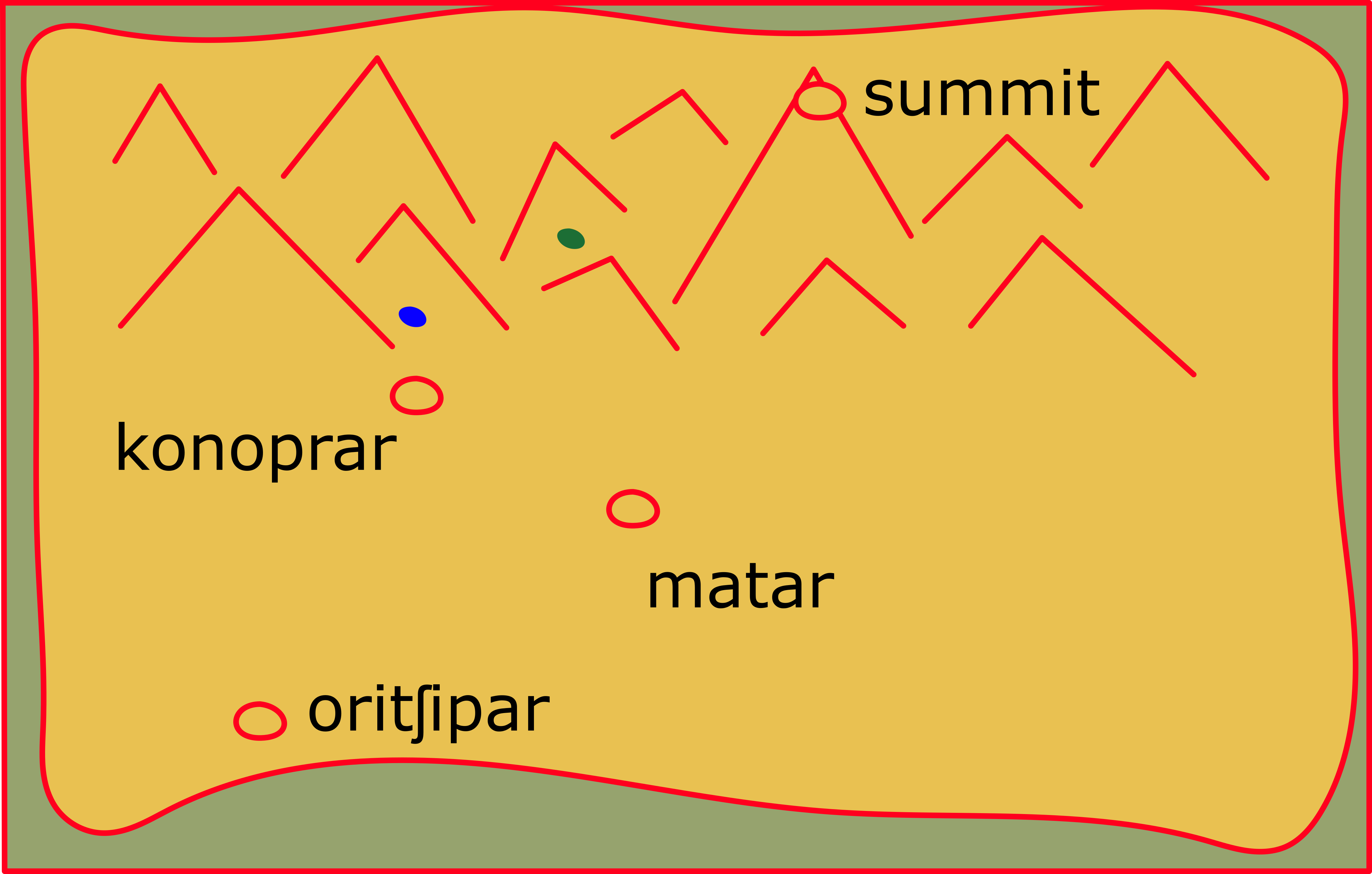

What I had expected based on what the Qwamaq had told me was that there were four quadrants of the country, and the mountains were only in the northwest quadrant. But the map that Dzhagltshau showed me had mountains going all the way across the top. Here's an extremely rudimentary mock-up of what her map looked like.

When I asked them how far they had gone, they showed me where I've added a blue dot (where they were when I left), and the green dot (where we are now). I've also marked the locations of places that I have been to or heard about. Dzhagltshau explained that the green around the edges is water (she used the toki pona word "telo," and then the Portuguese word "mar.")

The thing that confused me most was that in Matar and Konoprar, the mountains were only in one corner of the horizon, not across a huge portion of it, as this map would suggest. I was having trouble conceptualizing how it worked.

I tried to ask if the map was to scale, but I was having trouble figuring out how to ask it. Finally I asked if the mountains were really as big as the rest of the land, and while Dzhagltshau didn't have a good answer, Zhoniker said "qap. tʃiˈkaŋil maŋˈŋapa fu sokaŋoˈper tar kweˈloʃ papaˌnolseˈmer." (No. The Olsem maps focus too much on the mountains).

Dzhagltshau retaliated, using ejectives to the same effect as an English speaker may yell: "kʼorokʼa! aʃaˈfiri ʃuŋˈŋapʼa tʼar sokʼaŋopʼer fu aˌnolseˈmer!" (obviously! The mountains are very important to the Olsem!)

Zhoniker backed away slightly. "ʃoˈfiri, ʃoˈfiri, pwiripwir" (yes, yes, they are important, sorry.) His plosives were so lenis I could hardly hear them. It almost sounded like "wiriwir." Zhoniker then said, this time more directed to me, "uˈnalap qap tar kweˈloʃ papaˌnoritʃiˈper." (The Oriti maps are not similar).

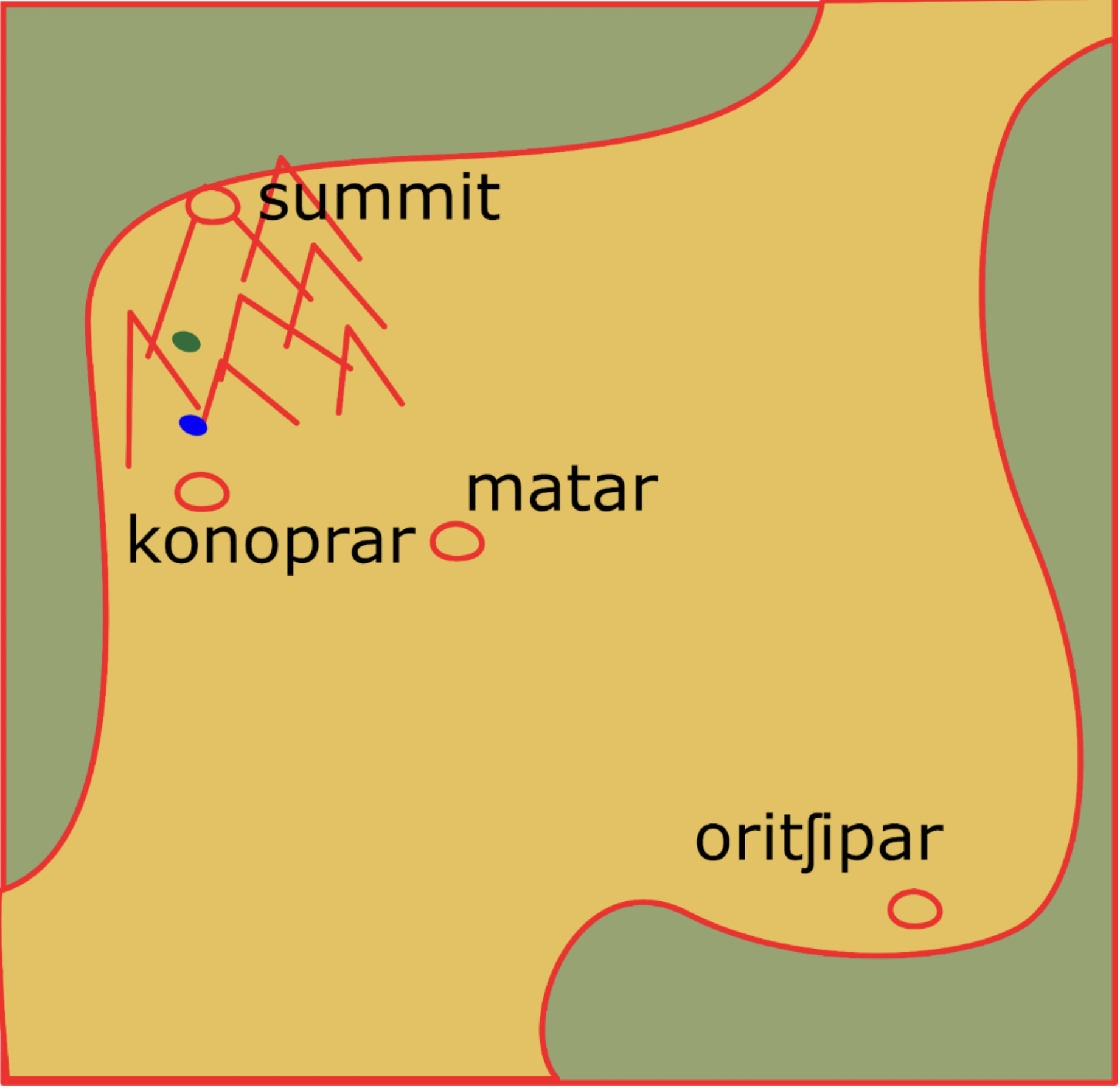

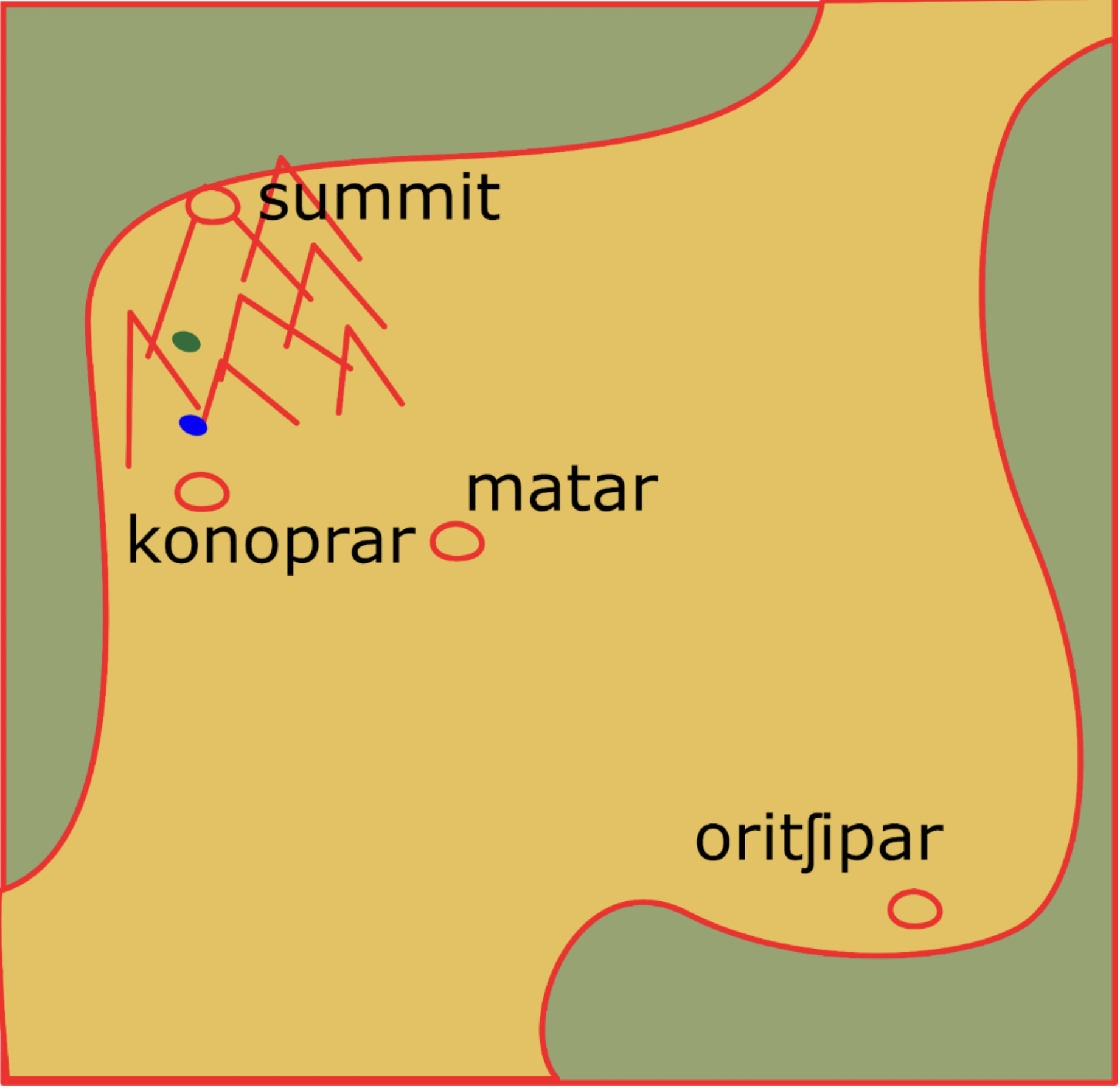

I let him use a pad of paper I brought and he drew something that seemed more representational.

It was actually really interesting to see the differences between the two maps. Apparently the Qwamaq don't usually draw maps and instead use settlements as landmarks. Almost every settlement has some unique feature. For Matar, it used to be a greenhouse. For Konoprar, well, there are probably a lot of them. For Ishimar, it was their unique pottery. Who needs a map when you already kinda know your way around?

But the Olsem move around so much that they need to be able to tell where they are. The mountains at the bottom of the range on the map help the Olsem orient themselves. Apparently, even in Oritshipar, you can still see the closest mountain to you, and a few others near it. This closest mountain serves as a landmark.

The Olsem also travel in straight lines away from and back to the mountain. During the journey of an Olsem, the same mountain will be close to them the entire time, until they return to the mountains. They used to migrate mostly east, but they've started migrating south and southeast instead because the land to the east of the mountains is occupied by Oriti settlements.

If an Olsem strays off course and the "closest mountain" changes, the balance of chaos has been upset. I think it's because before an Olsem leaves the summit of the mountains, Fulors will commune with the chaos god and instruct families on where to go, and which mountain will be their "closest mountain," and once a decision has been made, one must follow through with it.

The Olsem also NEED the maps to navigate through the mountains. Because it's hard to see landmarks reliably, people rely on the maps to tell them where certain mountains are and where the pathways between them can be found. This is why the mountains themselves take up half of the map, even though they actually occupy much less land. Once an Olsem leaves the mountains, they will likely not need the map very much as long as they keep track of which mountain is closest.

Honestly it's a lot to keep track of. I may provide an updated explanation if/when I learn Olsem or become more engaged with Olsem culture. Their perspectives and worship of chaos allude me, ever fading into the dark tapestry draped over the door to everlasting knowledge.

The Cave

Dzhagltshau led us off the path and over to a cliff that went very high up. Under the cliff was a cave. She reached into her pockets and withdrew a huge sack of salt, at least two pounds of it, and sprinkled a handful into the cave, muttering something under her breath. I asked, "tʃiˈka fu meˈlaq fimol?" (Why are you doing that with the salt?)

"tʃiˌkeʃi qap oʃi?" (You don't know?)

"tʃiˌkeʃi qap par fu fol?" (I don't know what?)

"esiˈʒaŋa tar tekwoˌtekwoˈper fu woɴˈqar paˌporiˈpaʃ" (Tekwotekwoper sits in the depths of the cave.)

Zhoniker flinched at the name drop, but I have no idea who Tekwotekwoper is. Dzhagltshau continued.

"foˌrifiˈʃi tar misiˈrer maʃa fu meˈlaq paˈpampaka fifi aʃapliŋ fu poŋer. ʃopaˌtekwoˌtekwoˈper raˈper paˈpʼakʼi. esiˈkiʃ maʃa tar misiˈrer fu woɴˈqar. ʃoˈkaʃu fu tekwoˌtekwoˈper. ʃoˈponki fufu aʃaˈpolemp ŋikiˈpam anʃi. ʃoˈsempa fufu ʃoˈproŋ fu raˈper paˈpʼakʼi" (The chaos god suppresses it with our salt when it rains. Tekwotekwoper is an ancient evil. The chaos god oppresses it in the depths. If we stop putting it, the ancient evil will return.)

Zhoniker said, "ŋir. ʃoˈpaŋa fu fwikiɴqiˈpoʃ. pwiripwir paˈʃum paˈpampaka." (wow, this custom is intense. Thank you for protecting us).

Dzhagltshau pinched her fingers together and made a downward gesture. "ˈpoŋim. tʃiˈqami tar fuˈlor. imiŋoli." (At least, that's what I've heard. it is said by the Fulors. It's unfalsifiable.)

Zhoniker made the same pinching downward gesture. "ˈʃoˈpoŋki fufu tʃiˈqami tar fuˈlor fufu ʃoˈʒaŋa. ʃoˈsempa fufu ʃoˈʒaŋa ˈkoroka. unˈkor qap kataˈfel fu mofofaq. ʃoˈpiŋa fufu ʃoˈfiri fu melaq ˈkoroka." (If the Fulors say it's real, then it must be! Maybe it doesn't write like fingers, but the salt must be important, it is obvious to me.)

Dzhagltshau shrugged.

Tangent: to "Write like fingers"

I didn't get this at first but in Qwamaq, to "write like fingers" means "to be a literal, denotative meaning." In this case, "it is possible that it doesn't write like fingers" meant "maybe there isn't LITERALLY a being named Tekwotekwoper that needs to be literally oppressed by the literal real tangible chaos god." Or something. This is my understanding, at least.

Tangent: Gestures in Qwamaqqar

I'm not sure if the gestures are unique to the Qwamaq or if they are also used by the Olsem, but Dzhagltshau and Zhoniker both made the same gesture while... correcting each other? Having conflicting thoughts? Disagree? Not sure. But it reminds me a bit of the Italinan pinch gesture, but it's more sideways? I think? Idk it's interesting though.

Jan 20 2025: Foraging in Four Languages

This entry might be difficult to read. I'm going to use a mixture of orthographical systems. Don't worry, they're all in the latin alphabet, but I will be using IPA for Qwamaq and normal latin for toki pona, English, and Portuguese. All of these languages pop up here. Dzhagltshau is a REALLY fast language learner, and she's learning all at the same time, mixed up. I am kind of in love with it.

"A gente precisa de kama jo e telo e fruit too," said Dzhagltshau. (We need to get water and fruit, too.)

The funny thing is that when you speak all the languages, this kind of thing doesn't hurt to listen to. Or maybe that's just me? I'm not sure. It's a really fun experience.

I replied. "ʃoˈpiŋa. Onde la fruit li lon? kin: qual fruta?" (good idea. Where will we find fruit, and also, what fruit?)

She responded. "Bem, mi te qami. maˈmiripi, how do you say fu tumpapaˈŋer em suas toki?" (Well, I'll tell you. Wait a sec, how do you say "berries" in your languages?)

"In English, 'berry,' plural "berries." Em português, sei lá… talvez 'frutinha'? é o diminutivo de 'fruta.' toki pona la, kili. kili li lili anu seme." (In english "berry," plural "berries." In português, idk… maybe "frutinha"? It's the diminutive of "fruita." And in toki pona, "kili." Like a small one, right? )

"Bem. o kama!" (Good. Come with me!)

She led me down a trail and pointed to a tree. "Veja." (Look.) She pointed closer and showed me some slashes carved into the bark, similar to a number sign, but more chaotic. "ʃoˈŋiki fu um fulor aqui tar isso. It signifies, 'não comer as… frutinhas de isso asoker." (A fulor put this here. It means, "don't eat the… berries of this tree."

She used incorrect grammar with the Portuguese, so I chuckled and corrected her. "não coma as frutinhas dessa árvore" (Don't eat the berries of this tree).

"Why 'coma'?? ʃoˈfuk ono par ta? 'comer' é um verbo de 'er,' né?" (Why "coma"?? Am I mistaken? Is "comer" not an -er verb?"

"é, mas quando você quer… comandar, poˈkiʃʃi fu sariˈpoʃ, eˈsalap fu kaŋiˈloʃ tar a and e no fim da palavra, li esun." (It is, but when you command, force with words, the a and the e swap places at the end of a word, and swap places.)

"Ah! I understand! Obrigada." (Ah! I understand! Thank you.)

"Alem disso, naʃimˈpaʃ. A fulor put isso aqui, kin lon kasi pi frutinhas boas. quer que tʃiˈpape fu frutinhas boas." (Anyway, the markings. A fulor put them here, and also on the trees that bare good berries.)

I will be honest with you, I have so many languages floating around my head that I don't remember whether or not "boas" in Portuguese is supposed to go before or after "frutinhas." But I am proud she got the gender right! Maybe Olsem has grammatical gender. Not sure.

She showed me how to find the right markings on a tree, and we collected berries. She also showed me a spring that ran down the mountain. The water was icy cold, and she explained that At the very top of the mountains, snow melts and becomes water. The act of melting is itself a manifestation of the chaos god, because snow and ice are ordered, but water flows free and is hard to predict without observing carefully in new environments.

We filled each of our gourds with water (including Zhoniker's) and returned to camp, where Zhoniker had finished decorating the circle we would sleep inside. He had explained to me a few nights before that while not strictly necessary, if creating circles to camp in periodically, it's a good idea to make a habit out of decorations. Each circle is a petition to spirits, and the spirits like stories. Spirits are patient, but not THAT patient.

His decorations consisted of little mountains in the direction of the summit, which we were probably one day's travel away from, and little creatures from all around the circle making their way to the summit. The three of us sang songwalker songs together before going to sleep.

tangent: some fun idioms used in this conversation

Dzhagltshau used "maˈmiripi" to mean "hold up," but it really means "make yourself north" or "make yourself high." No idea why this is. I guess I don't understand English's "hold up" either, and that has upward motion. Strange.

"ʃoˈfuk ono par ta" literally means "did I poison myself" or "did I lie to myself," but it is used as an idiom to mean "to be mistaken." Fits in well with fuk's conceptual metaphor of poisoning things being the same thing as lying to them. Oddly enough, I've heard this specific idiom used as much with inanimate objects as with people. How curious.

"eˈsalap fu kaŋiˈloʃ tar X tar Y" Literally means "X and Y dance inside a circle," but it's used to mean "swap places" or "trade out." I emphasized my usage of this with "esun" in case I got it wrong, but I didn't! Nice.

Jan 21 2025: Arrival

Finally, after such a long journey, we arrived at the summit. Or, well, at the foot of one of the four summits. As I looked around it became apparent that while we were at the foot of the tallest mountain, there were several other nearby peaks that had similar structures built upon them. It reminded me a bit of the Alps during the summer, but if there were more ruins. Zhoniker was getting cold, so I popped back to Saint Paul and brought him some blankets from my home. Dzhagltshau was already bundled up, and I have a weirdly high cold tolerance, so I was mostly fine.

There were bits of snow here and there packed into corners of split boulders. It seemed like it was cold enough that the snow up here wasn't melting much, but it didn't feel too cold, and there were trickles of water from the snow that met in modest brooks and streams. Dzhagltshau told me that there was a grand river that flowed from the mountains due Southeast of the range, meandering through Qwamaqqar. Nothing comparable exists in Olsem lands, apparently; ponds are more common up there, and it rains far more.

I pointed to a much shorter mountain peak to the left of the tallest mountain. "umˈporop eˌlakiˈŋapa fu sokaŋoˈper tar aʃikaˈper. uh, ʃoˈporop akiˈŋapa fu ʃiʃraˈpampam paˌsokaŋoˈper." (This mountain seems older than the others. Uh, the ruins of the mountain do.)

Dzhagltshau explained. "esiˈtaka qap tar ikriˈfer fu swikokaŋoˈper fifi ʃoˈpakʼi." (Nobody settles there periodically because it's so old.)

"aʃaˈsel ampar ʃuˈqap," (let's go there), I said. I can't quite explain the feeling, but the mountain was calling to me, as if my heart was a pendulum; every time I looked at it, I could feel myself becoming excited. Zhoniker and Dzhagltshau obliged. After all, we weren't in a hurry.

But nothing could have prepared me for what I actually found up there. Adorning the walls were lines and lines of Biblical Hebrew. Though the stone had eroded, some inscriptions were big enough to read. The prayer ברוכה את תהום was carved everywhere. Once I noticed it, even the oldest inscriptions of that prayer became readable to me. This is the beginning of the prayer I use to open the gates.

But the strangest of all were the old clay pots everywhere. Not only did they have Hebrew written all over them, but this writing had niqqud. Niqqud was invented no more than 1300 years ago in Europe. That means that people who could read and write Hebrew were here at least that recently. Of course, that's still a really long time ago, but the Hebrew script is much older, so this gives us a much better time frame for "most recent Hebrew speakers in Qwamaqqar."

Finally, in one of the ruins, I found an ark holding a fully intact torah. It was beautiful and protected in an old velvet cloth. I know you're not supposed to do this, so don't tell my rabbi, but I opened the torah and began to read from it. Yep, moses was everywhere.

"tulik eɴˌqwamaqifaˈqel par epi. ʃoˈmaŋi fufu tʃiˈpako qap. pwiripwiripwir." (I tried to translate it but I don't understand it. I am so sorry.)

"ʃoˈpiŋa fufu tʃiˈpako epi," (but I can understand it), I said. "poˈqolinʃi fu 'Torah.' ʃopaˌmekeˈnoʃ-paˌpaŋkaˈper-paˈpaka epi." (It's called a "torah." It's a book of my ethnic group.)

I told her all about the tanakh best I could. At the time of writing, I think she understands that it's a holy book, but trying to explain a "story" in a language that doesn't have a word for "story" is kind of hard. It's a thing that isn't true that people tell each other. Or maybe it is true. Like the Olsem and Qwamaq certainly have stories, they just don't have a word directly for them. (At least the Qwamaq don't.)

The last thing I found in those ruins was an old scroll. Most of it was burnt, but a very small section of it was still legible. It was written in Hebrew. It said:

ותקרא תהום לנו ונמצא חן בעינה ונשנן את סכנינו

וַתִקְרָא תְּהוֹם לַנ֔וּ וַנִמְצָא חֵן בְּעֵינָ֑הּ וַנִשְׁנָן אֶת סַכִּינֵֽינוּ׃

vatikra lanu t'hom vanimtsa khen b'enah vanishnan et sakinenu

and-called.3sgf to-1pl Depths and-found.1pl favor in-eyes-her ; and-whet.1pl def.obj knife-pl-our

The Depths called us and she grew to like us. We whetted our knives.

The above is the first line visible, at the top left corner of the scroll. The second line is my attempt to add niqqud and a few cantillation markings based on my knowledge of Biblical Hebrew. The third line is a transcription. The fourth line is a gloss. The fifth line is an English translation.

I'm going to try my best to transcribe, parse, and translate the rest of the non-burnt portion.

Olsem Families

When we finally reached the top of the tallest mountain, I asked Dzhagltshau where we could find the family that the coin belonged to, and she cut me off and went on a really long tangent. I'll just summarize it.

There are twenty eight Olsem families. The family you belong to is determined by your mother, not father, but other than that, it's quite reminiscent of Hmong families.

You can only marry outside of your own family. Even if you're related by blood, it's considered socially acceptable to marry someone, as long as you are classified under different families. Usually men marry women. Once a man marries a woman, he becomes part of her family, but remains part of his own as well.

Apparently these trinkets are also traded a lot between families, and households. Different households exist within each family, and the number can fluctuate. These households are composed of smaller groups of parents and children who travel together, and nomads who travel alone, such as Dzhagltshau or fulors. These "households" come together and live in the well-kept ruins for about a month every year.

So the first step is to find which of the many households of this family this trinket belongs to. And no, it's not Dzhagltshau; she has read all of the documents her household owns and none of them mention Dora.

I asked, "ˈtoˈporem tatar ˈtufuŋ ampar fu ʃiʃraˌpemˈpampam takaˈŋapa ta?" (We should search each ruin one by one, right?)

Dzhagltshau responded, a bit upset. "fol? ta ʃoˈpuri un fufu esiˈkolwa tar naqer iʃ fu ʃiʃraˈqar papaˈler? soˈsawe fu ʃannaˈper paˈpaka! ʃoˈpasoke ifomwaqˈqar priˈkoʃ paˈpiʃ." (What? Do you wish to break into someone's home? Absolutely not! Your suggestion is insane.)

Zhoniker chimed in. "esiˈkeʃi fu mipriˈqar tar Dzhagltshau. ta esiˈkolwa fin naqer tar paˈler fu ʃiʃraˈqar paˈpiʃ, esiˈka anʒa toraˈqar? ta tʃiˈlif oʃi epi? ˈsaliʃ." (She's right. Do people break into your house where you're from? And are you okay with it? You should already know this.)

I said, "qap. esiˈʒaŋa fu ʃapatuɱfaq oʒa. koroka toˈratʃi ampar." (No. That is illegal. The logic follows that we'll wait.)

Zhoniker nodded. "toˈporem ono tatar aʃaˈproŋ oʃi fu toraˈqar. tʃiˈʃum ano ʃuqa. esiˈmiʃ tar aˌnolseˈmer fu pomˈpompomˌpompiˈper" (I think you should return to Toraqar. We will be protected here. It should be three eight-day-cycles until the Olsem arrive.)

I nodded and said my goodbyes, and left.

Tangent: idioms in this chapter

"takaˈŋapa" means "one by one," but it literally means "in the mannar of embroidery."

Dzhagltshau says "esiˈkolwa fin naqer oʃi fu ʃiʃraˈqar papaˈler" to mean "you break into somebody's house," but it literally means "you snap {still very unclear on the meaning of naqar} in half, in somebody's house." It's just an idiom.

"soˈsawe fu ʃannaˈper paˈpaka!" means "absolutely not," but it literally means "cut my thread" (as a command).

"ʃoˈpasoke ifomwaqˈqar priˈkoʃ paˈpiʃ" means "your suggestion is insane," but it took me a really long time to figure this out originally. This is apparently a clipping of "asoke ifomwakriperiqar." Long story short, that means "to become a bad head." But that means "insane."

"esiˈkeʃi fu mipriˈqar tar Dzhagltshau" means "Dzhagltshau is correct," but it literally means "Dzhagltshau knows in the northern direction."

"pomˈpompomˌpompiˈper," broken down, is the root poŋ (which means "be a square" in modern qwamaq) reduplicated such that there are four of them. Two would mean "day," and three would mean "four day cycle." the "pi" is from "fi," the infix for "three."