Introduction

Who

This grammar was written by lipamanka, known among the Qwamaq as "Toraper." Toraper means "one who comes from another world" and the root "tora" comes directly from Dora Lipman's name. For the remainder of this grammar, lipamanka will be referred to as "Toraper." Toraper uses it/its pronouns in English.

Lipamanka collaborated with Zhoniker when creating this grammar. Zhoniker is a native speaker of Qwamaq who speaks Qwamaq, Olsem, and Oriti as his first languages. Zhoniker uses he/him pronouns in English.

Lipamanka also collaborated with Dzhagltshau, an Olsem linguist and polyglot who speaks Qwamaq fluently.

Also in collaboration but less so are Akakiper, Zhoniker's grandmother (though kinship works differently for the Qwamaq, so this is somewhat misleading); Uqumer, Zhoniker's mother, and the children Ripiper and Usalamaper. I've been visiting them daily for the past two weeks documenting their language. Akakiper was particularly useful in some word etymologies, because she is quite venerable. (Her name literally means "rock-rock" because rocks are old.) I've met and spoken with countless other Qwamaq folk who will not be named.

Qwamaq (called "Qwamaqifaq" or more formally "Qamifaq Paqwamaq" natively) is spoken by the Qwamaq (who call themselves "Anqwamaqer" natively). They live on Qwamaq land (known as "Qwamaqqar" natively). Many members of the Olsem (a nomadic ethnic group that lives in the mountains to the North) also speak Qwamaq.

There is kind of a dialect continuüm? But it isn't based on from city to city, it's more based on how rural the speakers are. Rural dialects seem to be more conservative, according to Zhoniker. He told me that he spoke "like [his] grandmother" and that people in the cities talk weird. (He actually said that their version of Qwamaq was "set ablaze" which is fucking fantastic!)

When

First published in October 2024. This is a living document though; last edited in May 2025. I will continue updating it (especially the dictionary part) as I learn more words and have the time to transcribe them.

Why

I have an ongoing project where I document my efforts to find out what happened to my great great aunt, Dora Lipman. She went missing in 1953 and I've confirmed that she got stuck in this world after opening a portal.

I want a reference document that not only I but also others can reference if they have questions about how Qwamaq works and want to parse snippets that I use in my journal so I don't have to gloss all of them.

People have also said that they want to learn Qwamaq. Hopefully this will help them!

What

This document will be split up into the following sections:

Phonology

Word Classes and Derivational Morphology

Syntax

Phatic Phrases (phrasebook)

Registers

Lexicon/Usage is available here.

Illustrative Examples (all of which are from first language speakers)

Orthography

Phonology

|

labial |

coronal |

dorsal [-back] |

dorsal [+back] |

| nasal |

m |

n |

ŋ |

|

| plosive |

p |

t |

k |

q |

| fricative |

f |

s ʃ ʒ |

|

|

| ""liquid"" |

w |

l ɾ |

|

|

Vowels: a e i o u

All phonological rules are based on the completed forms of inflected words. That means that all affixes are appended to roots BEFORE any of these rules take place.

There is one unordered phonological rule: DORSAL CONSONANT HARMONY. Backness spreads leftwards through dorsal plosives. Transparent to everything.

As for ordered rules, first nasal assimilation. Nasal stops assimilate in place to any consonants that follow them. For whatever reason l is also part of this and becomes a nasal before another consonant. Before f, nasals and l become ɱ, and before q, nasals and l become ɴ. Nasals and l assimilate to m, n, and ŋ as well before bilabial, coronal, and velar sounds respectively.

Next, syllabification occurs.

CCVC

appendix word finally; cannot be w, l, or r.

onset cluster condition: second consonant in a cluster must be w, l, or ɾ; the first consonant in a cluster must be an obstruent

coda condition: coda must be a place linked nasal or l or exactly the same as the sound that follows it (creating a geminate). (bleeding relationship with nasal assimilation)

stray syllables fixed through epenthetic i and p; words lacking an initial onset are appended with a glottal stop.

this has a bleeding relationship with nasal assimilation.

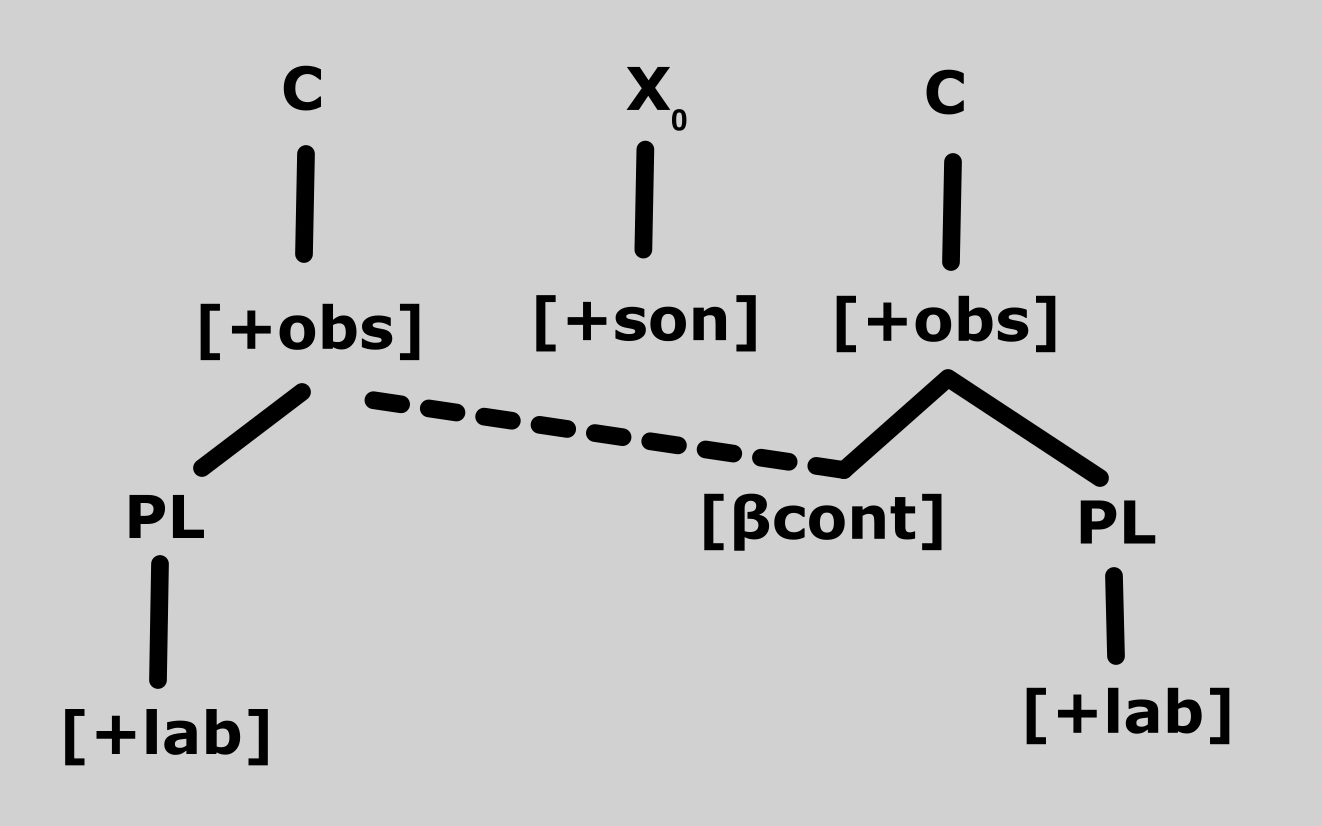

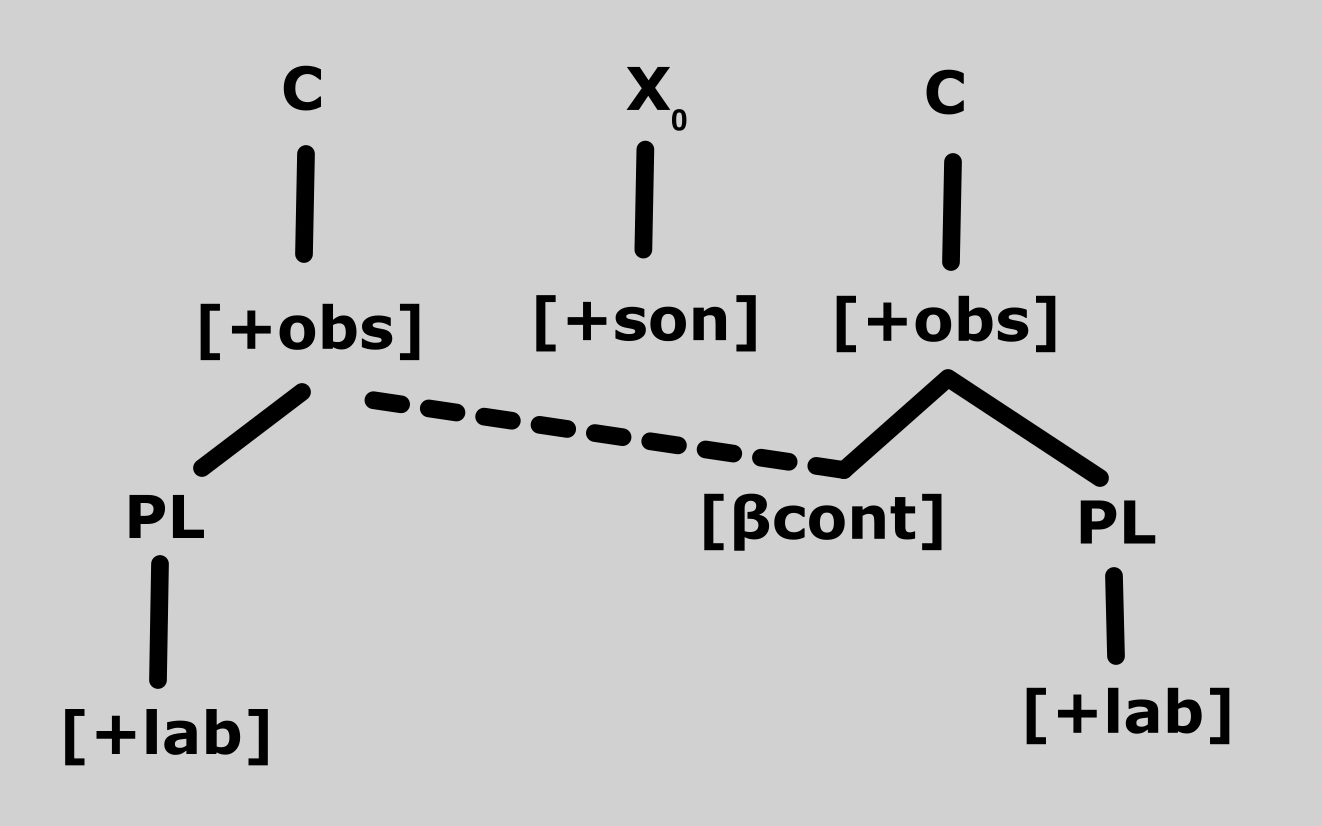

Then, labial consonant harmony: continuity spreads leftward between labial obstruents. Transparent to sonorants, opaque to obstruents. This rule has a feeding relationship with syllabification.

Then, plosive dissimilation: If (ignoring vowels), three plosives in a row are of the same place of articulation, the middle one will become t. This has a feeding relationship with both the epenthesis in syllabification and labial consonant harmony.

Then, palatalization: t becomes tʃ before i. This has a feeding relationship with plosive dissimilation.

Any time after syllabification, stress patterning occurs. The first syllable of each morpheme receives secondary stress. The first syllable of the last morpheme receives primary stress. This has a feeding relationship with syllabification.

My collaborator (Zhoniker) is from a small town called Matar, but he made an impression of urban Qwamaq for me. It seems that the major difference is that all vowels become o before uvular consonants. This has a feeding/bleeding relationship with dorsal consonant harmony. They also use [h] word initially where rural Qwamaq would use [ʔ].

Word Classes and Derivational Morphology

Word Classes

Lexically, Qwamaq has pronouns, verbs, adverbs, and prepositions. Surprisingly, there are no exceptions to this rule! This means that all roots with semantic meaning are either a verb or an adverb. There are also numbers. I'm going to define these lexical word classes below.

However, Qwamaq doesn't entirely lack nouns or adjectives. Qwamaq features a lot of nominalizers that are almost always suffixes (with the notable exception of the "ethnic group" circumfix and the archaic plural prefix). There are also adjectivizers. There are productive, semi-productive, and nonproductive affixes.

Nonproductive affixes are affixes that are only used in specific lexicalized compounds and are never used in neologisms.

Semi-productive affixes are used in many lexicalized compounds and are used to form neologisms, but cannot be used without creating a new lexical entry.

Productive affixes are used all the time without creating a new lexical entry.

My methodology for judging productivity was pretty simple:

I tried using these affixes in productive ways that I came up with and saw if I got corrected or not (they treated me like a child speaker and corrected me when I said something that was wrong)

I introduced them to things from my world and discovered how they created neologisms for them

I suggested my own neologisms for objects from my world and paid attention to their reactions

I will say that my analysis of parts of speech in Qwamaq is a little abstract. None of these verb roots appear on their own. They are ALL bound morphemes. Some of them I've never heard used as verbs and only in nominalizations. But my analysis is extremely consistent, which is why I'm using it.

Stative verbs can be appended in between a root and a nominalizer to incorporate as an adjective or a patient of the verb. For example, a root with a meaning for "to be red" can be put between a verb meaning "to beat with a stick" and the instrumental nominalizer, becoming "red stick." Alternatively, a common name for children is /usala-ma-er/ [ˌusalamaˈper], where "usala" means "climb (transitive)" and "ma" means "tree," so the name is something close to "tree climber." This is completely productive, but some compounds created this way have become lexicalized and cannot have productive meanings.

Any noun can incorperate an auxiliary verb to change the meaning; these are always appended at the beginning of the word.

When I make a dictionary for the language I will try my best to include all of the lexicalized compounds I can, mostly for myself but also for anyone who wants to learn Qwamaq.

It is by far more common to see stative verbs with descriptor meanings incorporated into nouns like this than to see them relativized as verbs with /maf-/, but both are common. Zhoniker says that in urban dialects, /maf-/ constructions are actually more common, and the demonstrative infix is shortened from /C-wik-V/ to /C-w-V/ because relative clauses are more common. /maf-/ is also shortened to /f-/.

Noun and Adjective Derivation

All nouns, some adjective forms, some adjectives, and some verbs are derived using these affixes. Nouns are derived with nominalizer affixes. Some adjective forms are derived from either verbs or nouns using adjectivizer affixes. The meanings of verbs can be changed with some affixes as well.

I've separated these into three categories: general, specialized, and archaic. General ones are used frequently with general meanings, specialized ones are more specific, and archaic ones only exist in older lexicalized compounds.

GENERAL DERIVATIONAL AFFIXES

| affix |

Function |

Meaning/Notes |

productive? |

| /-er/ |

agentive nominalizer |

general |

semi |

| /-oʃ/ |

patient nominalizer |

general |

semi |

| /-el/ |

dative nominalizer |

general (but much less common than the others) |

semi |

| /-pam/ |

ablative nominalizer |

general (but much less common than the others) |

semi |

| /-qar/ |

locative nominalizer |

general |

semi |

| /-faq/ |

instrumental nominalizer |

general |

semi |

| /-ŋapa/ |

comparative adverbizer |

creates adverbs (similar to "in a _ manner" in English) |

semi |

| /a-/ or /i-/ |

stativizer |

added to the beginning of any nominalized verb. Turns it BACK into a verb meaning "to be [noun]." More on this in the syntax section.

Both allomorphs seem to be exactly the same |

yes |

| /pa-/ |

general adjectivizer |

kind of like "of." used productively to turn nouns into adjectives. it reminds me of the genitive case in some languages, and you may see me gloss it in places as a genitive affix even though that's not QUITE what's going on.

Can be appended to pronouns, but those pronouns are always in the oblique. |

yes |

| /maf-/ |

relative adjectivizer |

opens a relative clause that is grammatically the same as an adjective whose head is the verb it appends to |

yes |

| /-nʃ/ |

abstract nominalizer |

"the abstract concept of X" |

yes |

| /-anʃ/ |

occurative nominalizer |

"an instance of X happening" (you'll often see this followed by an adjective formed with /pa-/ to act as one of the objects) |

yes |

| /-um-/ |

negator |

negates an embedded adjective. Goes after the adjective and before the nominalizer. Can also negate the base root verb in a nominalized verb. |

yes |

SPECIALIZED DERIVATIONAL AFFIXES

| affix |

Function |

Meaning/Notes |

productive? |

| /-meleʒ/ |

market locative nominalizer |

used for "place where this is traded." Added to the ends of words for shops, market stalls, restaurants, etc. |

semi |

| /-ram/ |

abilitive adjectivizer |

This might have inanimate connotations |

semi |

| /-ufi/ |

abilitative adjectivizer |

This might have animate connotations |

semi |

| /-paʃ/ |

past tense patient nominalizer |

Just like /-oʃ/ but "was the patient" instead of "is the patient." I think it's used more productively than most affixes, but not fully productively except for words that already have forms with /-oʃ/ or another patient nominalizer. |

yes? |

| /-aro/ |

negative agentive nominalizer |

like /-er/ but negated. Not very common but similar to /-paʃ/ can replace /-er/ in a noun productively. |

yes? |

| /-onta/ |

food nominalizer |

Used for the names of dishes. Only productive for loans and neologisms (which are uncommon for dishes). Only ever used in lexicalized compounds. |

not really |

| /an-er/ |

ethnic grouped nominalizer |

turns a root "to be a member of X ethnic group" into "X ethnic group." Its only productive usage is as a joke, similar to calling a bunch of oranges "the orange nation." I think it's pretty funny personally. |

no |

| /-kor/ |

animal agentive nominalizer |

"animal that does X." used in a lot of words for animals. only productive in the sense that IF a new animal was introduced to the Qwamaq, they would use this affix, but that would seldom happen. I only know this because I brought pictures of Elephants and Anteaters and stuff and had them come up with names for them. People seemed to turn to Akakiper to decide the neologisms. |

semi |

| /-kwam/ |

edible plant nominalizer |

"Plant that does X and is edible." Similar to /-kor/, it is used sometimes in neologisms, but not for all edible plants. |

semi |

Part of me wonders if some of the more specific ones of these are actually nouns. Like that analysis could work. But I doubt that this language would have bound noun morphemes.

ARCHAIC DERIVATIONAL AFFIXES

| affix |

Function |

Meaning/Notes |

productive? |

| /-ar/ |

settlement locative nominalizer |

used exclusively in the names of cities, towns, and villages. Based on the names of some of these settlements, it PROBABLY used to be productive. |

no |

| /an-/ |

old plural marker |

I've only seen this used with /-er/ to mean "The entire ethnic group" when the root verb means "to be a member of X ethnic group" and in a couple of other lexicalized compounds. It also seems like it used to be affixed to singular pronouns, which is where the current plural pronouns come from. |

no |

Pronouns

|

1sg |

2sg |

3sg |

1pl |

2pl |

3pl |

| direct |

ono |

un |

epi |

ano |

an |

ampi |

| indirect |

par |

oʃi |

oʒa |

ampar |

anʃi |

anʒa |

| oblique |

paka |

iʃ |

maʃa |

ampaka |

inʃ |

amaʃa |

There is also the interrogative pronoun /fol/

The infix /C-wik-V/ is a demonstrative that is appended after a consonant and before the first vowel after a consonant in a word. (So if the word starts with a vowel in UR, it will be appended before the second vowel). Speakers avoid using this though, this type of infixation in the middle of a morpheme is weeeiirrdd.

This is also one reason why people avoid relative clauses when possible and use things like parataxis instead; This infix must be added to the word being relativized.

Urban speakers, according to Zhoniker, don't avoid /C-wik-V/ (which is shortened to /C-w-V/) anyway as mentioned above.

Adverbs

General Adverbs

| Adverb |

Meaning |

| amaʃa |

together (same as 3pl.obl), sometimes ʃuˈpamaʃa |

| paka |

alone, solitarily (same as 3sg.obl), sometimes ʃuˈpaka |

| qap |

negator. See syntax section for more info about when/where. Note that when negating nouns, qap takes the productive adjectivizer /pa-/ and becomes paqap. |

| fimol |

why, where, how (interrogative; from /fim-fol/) |

| empiŋkiʃ |

quickly (lit. "with being brave"); from /emi/ and /piŋk-nʃ/ |

| ʃuqa |

here, now (from the older locative preposition "ʃu" and "qamel" which means "interior of a house"). |

| ʃuqap |

portmanteau of ʃuqa and qap. means "over there." Likely evolved when "ʃuqa" meant "in a house," and "ʃuqa qap" meant "not in a house." |

| ʃuŋŋapa |

very (literally "many-ly") |

All adverbs here can be placed anywhere in the sentence (except for in the middle of a prepositional phrase) and still modify the main verb. Even so, they usually appear at the beginning or end.

Temporal Adverbs

| Adverb |

Meaning |

| ʃumeʃ |

today, on that day |

| ʃipi |

soon (from ʃu ipi, "in" "to be close") |

Evidential Adverbs

| Adverb |

Meaning |

| emeʃ |

"I'm pretty sure but not positive" |

| emeʃa |

"godwilling" |

| ipenta |

"and I was told by someone who should know" |

| posiŋkak |

"but I don't remember if that's true" |

| imiŋoli |

"I don't think this is true but I have no proof it isn't" |

| poŋim |

"I heard this by word of mouth so who's to say" |

| fukiŋapa |

"and I'm lying to you"

/fuk/ fuk means "to poison" or "to lie." Even though fuk has negative connotations, this evidential doesn't, and simply says that the statement isn't true. |

| saliʃ |

"I'm telling you this but you should already know it" |

| efeliŋ |

"I may be exaggerating a bit" |

| koroka |

"This seems obvious, the logic fits" (often used as an interjection between sentences similar to "thus") |

| epref |

"I am approximating" |

Numbers

The Qwamaq seem to have some sort of base 20 number system, but they hardly ever use it day to day and instead opt for using ʃul and ʃuʃul (many and a large quantity, respectively), and often ʃulum or ʃuʃulum when embedded (not many, not a large quantity). While these quantifiers are not often embedded, I have yet to see the numbers not embedded. Below are infixes in underlying representation.

As far as I can tell, there is no difference between cardinal and ordinal numbers and it's just up to context. The fifth pig assumes that there are five of them, I suppose? This has led to some confusion though and I don't yet know how the Qwamaq resolve it.

| aŋka |

pel |

fi |

iʃi |

waŋ |

pi |

omm |

kaCi |

immo |

kwiʃ |

| akwa |

moqo |

orol |

futa |

inli |

amaŋ |

oriʒ |

omp |

eliŋ |

fakka |

Note that kapi is /kaCi/ underlyingly and the C assimilates to the following consonant (after syllabification) when embedded. This took me a while to figure out because of how uncommon numbers are.

If one wanted to list these numbers in order, they would need to embed them in between "ka" (thing) and "-er" or "-oʃ" (nominalizers).

Prepositions

There are actually a lot of these as far as I can tell, but speakers avoid most of them like the plague. The ones that you will likely see in every conversation are:

| case |

noun phrase |

clause |

| direct |

fu |

fufu |

| indirect |

tar |

tatar |

| oblique |

fim |

fimfim |

The "clause" column is for reduplicated forms of each preposition, which are used when the prepositional object is an embedded clause. (The first m in fimfim is actually pronounced [ɱ] which is fun! But this is common in any language that allows a labial nasal to occur before a labiodental fricative.) When speaking quickly people shorten fimfim to fifi which is really cute.

ALSO! It may make more sense to analyze fim as a prefix because the m assimilates to consonants that follow it during nasal assimilation, which normally doesn't happen over word boundaries (otherwise I'd expect liaison instead of glottal onset).

Others I've seen are: emi (comparative "like" "as"), ʃu (locative "in" "on" "at" "about" "with" "alongside"), en (dative "to" "towards" "for"), fo (ablative "from" "because"), and or (instrumental "using"). There may be more. But speakers do really avoid using these.

Zhoniker says that in urban dialects they are more likely to use them, but since visiting Konoprar, I haven't found this to be the case. It may be more regional than I thought.

Intensification

The most common intensifier is to code switch into "young speech" (see the registers and varieties section for more info) and pronouncing the intensified word with ejectives. This causes people to sometimes found roundabout ways of talking about things they want to intensify if they don't have a plosive in them, but most nouns have a plosive in them (through epenthesis or in the nominalizer), so it usually isn't too much trouble. Speakers will also ejectivize other obstruents, and devoice ʒ in order to do this. This means that ejectives are like, kind of phonemic? But that is a weird analysis in my opinion.

Another way is to modify a noun with ʒir, which people resort to sometimes when a noun doesn't have any plosives to ejectivize.

Syntax

Triggers

Qwamaq uses trigger based alignment, also known as Austronesian alignment. Triggers on the verb determine what type of constituent information the direct object is. Then, the remaining types of constituent information are assigned to the remaining cases in order of the primary hierarchy. There are three base cases: direct, indirect, and oblique. There are also three base constituent types in the primary hierarchy: actor, patient, and oblique.

Here are a list of all the triggers used Qwamaq:

| Indicitive |

Imperative |

Constituent Information Type |

| ʃo- |

ap-ŋa, ma- |

actor/sole argument |

| t- |

so-, m- |

patient |

| aʃa- |

en-ŋa |

dative |

| to- |

to-ŋa |

ablative |

| es- |

es-ŋa |

locative |

| po-ʃi |

po-ŋa |

instrumental |

| un- |

un-ŋa |

comparative |

You may notice that each of these has a derivational affix associated with it. I'm not really sure how well they match up though; These labels are just words I thought described the type of information well enough. Sometimes, derivational affixes won't really make sense, but these are all completely productive and NEVER produce lexicalized meanings. Any verb can take any of these.

Some verbs change meaning when certain triggers are used, but that's only because of the nature of prepositions. English does the same thing, like how "I spit water" means something different from "I spit at water." A lot of these don't make much sense, but they aren't lexicalized compounds because the meaning is part of the lexical entry of the root.

Changing JUST the trigger in one sentence can completely change the meaning. Let's take the following example:

/fuk/ - to poison, to deceive

/maper/ - tree

/ʃiʃ-wak-er/ - enemy

/puk-er/ - chicken

ʃo-fuk fu maper tar ʃiʃ-wak-er fim puk-er - The tree poisons an enemy in the presence of a chicken

t-fuk fu maper tar ʃiʃ-wak-er fim puk-er - An enemy poisons the tree in the presence of a chicken

to-fuk fu maper tar ʃiʃ-wak-er fim puk-er - An enemy poisons a chicken because of/while leaving the tree

aʃa-fuk fu maper tar ʃiʃ-wak-er fim puk-er - An enemy poisons a chicken for the benefit of/while approaching the tree

es-fuk fu maper tar ʃiʃ-wak-er fim puk-er - An enemy poisons a chicken under the tree

po-fuk-ʃi fu maper tar ʃiʃ-wak-er fim puk-er - An enemy poisons a chicken using the tree

un-fuk fu maper tar ʃiʃ-wak-er fim puk-er - An enemy poisons a chicken as a tree would

Mulitple Verbs in One Clause

I have heard people use multiple verbs in one clause. A fun thing they do is mark them all with different triggers. The direct object of the sentence is the direct object of ALL of the verbs, no matter what triggers they have. The indirect and oblique only grammatically apply to the last of the verbs in sequence, though. Sometimes from context it's clear what their relationships are to the other verbs.

To do this, a speaker puts all the verbs in ascending order of importance at the beginning of the sentence. Speakers avoid doing this with auxiliary verbs though, and I've only heard it a few times. I have verified through elicitation that it is a valid construction, though.

Word Order

The default word order in Qwamaq is VDIO (verb, direct object, indirect object, oblique object), but VIDO is also used somewhat frequently. DVIO and IVDO also happen on rare occasion, but only one constituent is fronted at a time, and unless the indirect object is being fronted (either before the verb or after it), the indirect object will always appear after the direct object. The oblique is never fronted before the verb, and doing so is considered ungrammatical.

Even though constituents can be fronted before the verb, almost every sentence fronts important information using a trigger. To avoid using the oblique (or, especially, other prepositions), speakers will almost always front information that isn't an actor or patient.

Here are some cases where the oblique or other prepositions may be used:

Some sentences just have a lot of different types of constituent information. In these cases, prepositions are used more readily than the oblique.

Sometimes a speaker will want to add extra information, but have already said the verb. In these cases, using the oblique is more common. If speakers want to clarify the meaning, they will repeat the sentence with a new trigger.

Instead of using the oblique or other prepositions, speakers may just repeat the sentence with the same verb, but change the trigger and give it a singular direct object. (Like, /es-fuk fu ma-er/ [esiˈfuk fu maˈper] is "the poisoning happened under the tree.")

TAM Auxiliary Verbs

There are a lot of these. There are two main categories, and they behave differently:

Optional tense/aspect auxiliary verbs. These are always completely optional and only CLARIFY the meaning without changing it.

aspect/mood auxiliary verbs. Removing these from a sentence will change its meaning entirely.

Because aspectual auxiliary verbs exist in both categories, I'll be calling these categories "tense" and "mood." It's worth mentioning that the way they work grammatically is exactly the same and this analysis is to show how optional these words are, not the differences in their grammatical usage.

Furthermore, for the sake of better explaining these auxiliary verbs on an anglophone audience, I've split category two into two parts: general and adverbial. Qwamaq uses auxiliary verbs for a lot of things that English uses adverbs for. Know that in Qwamaq, I am analyzing these two subsections as identical. I'm just separating them for an Anglophone audience.

Auxiliary verbs in the first category are always followed by a nominalized form of a noun. Frequently, this is locative, dative, or ablative, but some of them take less common nominalized verbs. In these situations, the nominalizers become completely reduced and compounds that normally have lexicalized meanings always lose it. A few auxiliary verbs take far less common nominalizers, like /-meleʒ/.

Auxiliary verbs in the second category sometimes take a direct object, that object being a sentence. They sometimes also take nominalized verbs like the first category.

These can stack completely productively!

TENSE/ASPECT AUXILIARY VERBS

| Verb Root |

Meaning/Nominalized Form It Takes |

| sel |

both future and past tense ("I will eat bread" "I have eaten bread"). It has perfective connotations and takes a dative nominalized verb for future tense and an ablative one for past tense. Can also mean "to go." |

| rati |

Progressive aspect ("I am eating bread"). Takes an instrumental nominalized verb. Can also mean "to continue" |

| kaŋil |

habitual/iterative aspect ("I have been eating bread, I be eating bread") . Takes locative. Means "to pace in a circle" otherwise. |

| olemp |

to start/stop doing something ("I begin eating bread"). Takes ablative for stopping, takes dative for starting. Means "to step" otherwise. |

| proŋ |

to redo something ("I re-ate the bread"). Takes dative. Means "return" otherwise. |

ASPECT/MOOD AUXILIARY VERBS

| Verb Root |

Meaning/Nominalized Form It Takes |

| asoke |

To come to do something, to begin doing something. Takes locative. Means "grow" otherwise. |

| orem |

To be obligated or expected to do something. takes an embedded clause. Ablative object is that which obligates or expects. |

| kor |

to be able, to be possible ("I can eat bread" "It is possible that I will eat bread"). takes dative. Means the same thing otherwise, just not being used as an auxiliary. |

| oŋki |

conditional ("If I eat bread" "when I eat bread"). Takes an embedded clause. |

| puri |

desirative ("I want to eat bread"). Takes embedded clause. Also used for "planning to" |

| kapwiŋ |

refusitive ("I refuse to eat bread"). takes ablative. |

| ulik |

attemptative ("I tried to eat bread" "I attempted to eat bread"). takes dative. Means "pull" when not auxiliary. |

ADVERBIAL AUXILIARY VERBS

| Verb Root |

Meaning/Nominalized Form It Takes |

| miŋku |

definitive ("I definitely eat bread"). Takes an embedded clause. |

| maŋi |

unfortunative/ ("It is unfortunate that I eat bread") Takes an embedded clause. |

| piŋa |

fortunative ("It is fortunate that I eat bread"). Takes an embedded clause. |

| faki |

unintentional ("A shawarma with extra tahini accidentally fell into my mouth"). Takes locative. |

| sempa |

hypothetical ("hypothetically, I eat bread"). Takes an embedded clause. |

| ʒir |

probable ("I probably eat bread"). Takes an embedded clause. |

| kuri |

possible ("It is possible that I eat bread"). takes an embedded clause. also used to turn a command into a polite request. |

Relative Clauses and Subordinate Clauses

Relative clauses in Qwamaq are formed by appending the infix /C-wik-V/ to the noun being relativized, and following it with the relative clause. The relative clause must begin with a verb, and the last affix to be added to the verb is /maf-/, which completes the relative clause construction.

Subordinate clauses are more simple. The preposition becomes reduplicated (per the table in the Word Classes and Derivational Morphology section) and the object of this new preposition is an entire new sentence.

Only the final noun in a sentence can be relativized, and only the final prepositional phrase in the sentence can take a subordinate clause.

Reminder: speakers avoid the infix /C-wik-V/, but it's still used from time to time, just avoided.

Valency Changing Operations

There are two valency changing operations: the passive and causative. They're both really simple.

Passive voice is created by omitting the direct object and skipping right to the indirect object. This differs from nominative-accusative language in the sense that any constituent information can be dropped, not just the "subject" (something that Qwamaq doesn't have). For example, if the trigger is /po-ʃi/, and the direct object is omitted, the instrumental object is being removed from the valent structure of the sentence.

In these cases, a preposition can be used to add back in the removed constituent without increasing the valency, but people don't usually do this unless the oblique preposition is still available.

Because functionally the passive construction is a nominative-accusative alignment language thing generally, this analysis is a little eurocentric. Keep that in mind. This is still a thing that happens.

Causatives are created using a few auxiliary verbs, listed below.

| Root |

Normal Meaning |

Auxiliary Meaning |

| kiʃ |

to force something physically (tr.), to push something (tr.) |

To force someone to do something |

| ʃiliŋ |

to place a layer of cloth on top of something (tr.) |

To cause someone to do something generally (like kiʃ without judgment) |

| klom |

to fill a bucket with many rock sized objects (tr.), to inspire someone (tr.) |

To inspire someone to do something |

| kor |

to grant permission (tr.), to be able to (TAM aux.) |

To allow someone to do something |

The dative object of these verbs is the action that is being caused, which itself takes its own direct object. The dative object is always backed. The dative object is marked by a reduplicated preposition, just like subordinate clauses. Consider the following examples:

/fuk/ - to poison, to deceive

/maper/ - tree

/ʃiʃ-wak-er/ - enemy

/puk-er/ - chicken

/aʃa-kiʃ tar ma-er fu-fu t-fuk fu puk-er tar ʃiʃ-wak-er/

[aʃaˈkiʃ tar maˈper ˈfufu tʃiˈfuk fu puˈker tar ˌʃiʃwaˈker]

The tree makes the enemy poison the chicken

/aʃa-klom tar puk-er fu-fu t-fuk fu ʃiʃ-wak-er tar ma-er/

[aʃaˈklom tar puˈker ˈfufu tʃiˈfuk fu ˌʃiʃwaˈker tar maˈper]

The chicken inspires the tree to poison the enemy

These are very similar to subordinate clauses and I'm not sure if it makes sense to analyze them as valency changing operations, but I was told that causatives are valency changing operations. I suppose there are two direct objects (one of which is the subordinated sentence) and two indirect objects, which in this analysis are all valent.

Conjunctives

Qwamaq connects pieces of information usually through juxtaposition, but a few conjunctive methods exist, usually using TAM auxiliaries. When two sentences appear in sequence, depending on which TAM auxiliaries are used where, the meaning can be more specific. These are the two consistent examples I've been able to find.

When an oŋki sentence and a miŋku sentence appear next to each other, it means "when (oŋki sentence), (miŋku sentence)."

When an oŋki sentence appears next to a sempa sentence, it means "if (oŋki sentence), (sempa sentence)."

When two sentences appear in sequence and the second one uses the verb maŋi, it means something similar to "but"

Comparatives

Things can be compared pretty easily using the comparative trigger or preposition, saying that they're similar. To say that they aren't similar is as easy as negating the verb. To make a different comparison that isn't "similar," these affixes must be appended to the words being compared. The comparative trigger is still used, these affixes just change the meaning of the comparative trigger or preposition from "like" or "as" to something more similar to "than."

| Affix |

Function |

Meaning/Notes |

| /o-/ |

positive numerical comparative |

"more of X" (appended to nouns) |

| /ŋ-/ |

negative numerical comparative |

"fewer X" (appended to nouns) |

| /el-/ |

positive qualitative comparative |

"more X" (appended to adjectives) |

| /nupor-/ |

negative qualitative comparative |

"less X" (appended to adjectives) |

| /ŋam-/ |

positive adverb comparative |

"more X" (appended to adverbs) |

| /onli-/ |

negative adverb comparative |

"less X" (appended to adverbs) |

These can be used without the comparative trigger or the comparative preposition.

Phatic Phrases and Pragmatics

This part is very underdone right now because I'm still trying to quantify them! I will add information here when have some compiled. Know that I intend on listing common phatic phrases (hello, goodbye, etc.) and how names work eventually.

For the time being here's a very informal explanation. Nobody chooses their own name in Qwamaq. Instead, others refer to you based on qualities you have or things you do. Any Qwamaq speaker can change anyone else's name at any time, but there are very complicated rules about when it is socially acceptable to do so, as well as what names can be chosen for which people and who is allowed to enact a new name for who.

When two Qwamaq speakers travel together, it is considered rude for them to introduce themselves. Instead, they introduce each other. Qwamaq avoid traveling alone for this reason, because telling someone what your current name is is slightly stigmatized, but there are plenty of situations in which it makes sense to do this, like if you're travelling alone or meeting someone for the frist time. You'd say "they call me XYZ" instead of "I am called" or "my name is" or something.

Registers and Varieties

A lot of these differences in registers have specific names IN Qwamaq, which suggests that speakers are aware of and frequently thinking about these things. It isn't an automatic linguistic practice, but rather a learned aspect of the culture.

This is common cross linguistically. Apparently it can take first language Japanese speakers well into their 20s to fully internalize and learn formality distinctions. Qwamaq is nowhere near as complex as that though, in my opinion. I've already gotten an intuition for all of these registers (except for the regional ones).

Sung Qwamaq

Sung Qwamaq is called qamishanngafaq /qami-ʃaŋŋa-faq/ [ˌqamiˌʃaɴɴaˈfaq]. When sung, Qwamaq grammar changes in a few key ways:

Most significant is that the productivity of all affixes, even the archaic ones, increases to "as productive as possible." My collaborator, Zhoniker, switches to the sung register a lot when we're alone together so he can use the affixes more productively. But he switches back to the spoken register a lot too, probably because using the sung register is kind of like if I told you to improvise a song with really good wordplay in it.

I've tried switching to the sung register, and it's actually really forgiving. Zhoniker corrects me relentlessly in the spoken register, but never in the sung register. Well, except for the word order. Sung register word order is VERY strict. It must be VDIO with NO room for changing anything, unless something is required to be backed for a relative or subordinate clause. Zhoniker still corrects that relentlessly.

Zhoniker also adds geminates after secondary stress. This feature also shows up in young speech.

The sung register is something that I think you can only switch into when speaking informally. Zhoniker avoids it around his mother and grandmother, but has used it in front of the children.

Formal Qwamaq vs Informal Qwamaq

The formality you use when you speak is actually not determined by age or experience. It's determined by tattoos. Everyone knows how to tattoo others, but it's forbidden to tattoo yourself. Someone else must tattoo you. It's considered very weird for a family member to tattoo you, so the relationships that result in tattoos are usually romantic, sexual, or very closely platonic (like, REALLY good friends, intimately so).

If you don't like a tattoo, you can remove it using a fruit called "diʒidiʒi" that only grows in the mountains to the north. It can be a little expensive, but keeping a paste made from it compressed on a tattoo will slowly remove it. Most people don't do this because tattoos are a status symbol and are often hard to acquire.

Zhoniker has one tattoo on his right arm. That means that when it comes to formality and respect, he's pretty low on the hierarchy. When I asked him about his tattoo, he looked embarrassed and told me that he used to be romantically involved with another man who was an aspiring songwalker, but he was really bad at it and Zhoniker only broke things off after several months of feeling too embarrassed to end the relationship.

The following day, Zhoniker asked if he could tattoo me. I said yes, and he did so. It was a beautiful dragonfly on my left forearm. Now, I can finally speak informally to Zhoniker without it feeling weird to him. Not that he actually cared before I got the tattoo; it just Felt Wrong because of how tattoos impact grammar.

And I suppose this means that Zhoniker and I are something similar to a queerplatonic relationship.

As for formality distinctions, here are the most significant differences between formal and informal Qwamaq (at least in rural areas):

In informal Qwamaq, it is really common to interrupt each other or start talking before someone finishes. This kind of reminds me of New York English, where it's considered rude to wait to start talking before someone finishes. In formal Qwamaq, there's a good two second break between people talking.

In informal Qwamaq, all geminates can be freely shortened (so qwamaqqar because qwamaqar)

In formal Qwamaq, while someone else is talking, the way you show that you're listening is by repeating the vocative phrase "miˈqami [name]." When I'm speaking to Akakiper, I nod along and say "miˈqami Akakiper" (or actually I can shorten it to "miˈqami Akiper," that is just a little more ambiguous because it can also mean "rock")

In informal Qwamaq, you repeat the direct object of a sentence as the person talks, reiterating the information they chose to mark as most important. If it's a first or second person pronoun, it's really weird to not change it around so it's still referring to the same thing.

You figure out when to use the formal or informal register by looking at how many tattoos someone has. People dress to display as many of their tattoos as they can.

It should be noted that when it comes to neologisms, it's expected for the member of the group with the most tattoos to decide for the whole group. Whenever I would show something new to the family I've been spending time with, everyone would always look to Akakiper. If she wasn't there, people looked to Uqumer instead, but Uqumer would frequently feel obligated to GO FIND Akakiper to ask her. It's really sweet how much they care about doing neologisms RIGHT.

They actually prioritize getting Akakiper to come up with neologisms over things like tending to food to keep it from burning. One time, Umuqer instructed me to get Ripiper, who was playing outside. (Zhoniker and Usalamaper were off somewhere and I was helping out around the house.) Then, Umuqer asked Ripiper to get Akakiper.

Why she didn't just ask me is beyond me, but it could be because Akakiper is a very respected member of the family and I only had one tattoo at the time, which was faint and covered up on my left shoulder. None of them had ever seen it. So formality-wise, I'm only slightly a rung up from the children, or perhaps even below because I'm not Qwamaq.

Old vs Young Qwamaq

"Young speech" has its own name in Qwamaq. It is called qamiminkifaq/qami-miŋki-faq/ [qamiˌmiɴqiˈfaq] (qami means "to talk" and miŋki means "young"). Non-young Qwamaq is considered the default, but I have heard qamiminkipumfaq /qami-miŋki-um-faq/ [ˌqamiˌmiɴqifuɱˈfaq] a few times to specify that one is not talking about young Qwamaq.

Note that the verb form "to speak young speech" is qami minkiŋapa. minkiŋapa is only used in this compound. To do something youthfully is usually a construction that uses the comparative trigger and a child as the direct object.

Anyone can speak young. To speak young is to speak with great enthusiasm. Adults in Qwamaq culture are expected to be passive and polite, but children are expected to be energetic and enthusiastic about everything. Once a child is able, it is expected of them to pronounce all plosives as ejectives unless they are low energy, i.e. tired or bored. I've also heard children add geminates after secondary stress (for example, [ˌqammiˌmiɴqqifuɱˈfaq]), just like in the sung register.

However, if an adult wants to, they can choose to use qamiminkifaq to show enthusiasm or excitement.

Rural vs Urban Qwamaq

I've been describing this throughout this grammar, but I thought I'd take a moment to compile all of the differences I know of based on what Zhoniker has told me, with the big disclaimer that I have not actually been to a Qwamaq city yet. Once I do, I will add that information here if I get the chance.

Zhoniker and Uqumer have both called the urban dialect "qamifaq paparamoʃ." When I asked them what paparamoʃ meant, they said that it was a city with walls. I asked them what param or aram meant as a verb, and they used a few words for "attack." So the root means "beseige," and paparamoʃ means "the beseiged" or "the beseigable" which is cool because the name of this variety is "speech of the beseigable." I wonder what the city folk have to say about this.

Zhoniker and Uqumer also had a name for the rural dialect: qamifaq papinker (language of the brave). Sounds pretty epic tbh.

I've already described some differences throughout this document, but once I visit Konoprar I'll update it.